Abstract

A rare association mature cystic teratoma (MCT) with endometrioma in the left ovary is reported in English literature. Coexistence MCT and endometrioma in the same ovary is extremely rare and its diagnostic is a challenge clinically and radiologically. To our knowledge we report the third case coexistence of a nonneoplastic endometrioma and benign neoplastic mature cystic teratoma in ovary.

Author Contributions

Academic Editor: Divey Manocha, Upstate Medical University

Checked for plagiarism: Yes

Review by: Single-blind

Copyright © 2017 DAROUICHI.M, et al.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Competing interests

The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

Citation:

Introduction

Association between mature cystic teratoma (MCT) and cyst endometrioma in the same ovary is extremely rare and less than five cases of this entity have been reported in the literature.

Teratomas, habitually named dermoid cyst, predominantly occur in young women. They account for 10-20% of all ovarian tumors and are bilateral in 10 to 15 % of cases 1. They arise in the ovary but can be located at the midline and in paraxial regions of the body and unusual locations, including lungs or ilea, were described 2.

Pathologically, they are composed of tissues derived from one or more of the three primitive germ layers and have often a cystic structure with a mean larger diameter of 8 cm. Typically it contains mature tissues of ectodermal (skin, brain), mesodermal (muscle, fat) and dermal (mucinous or ciliated epithelium) origin 3. The initial biological event that leads to teratoma is not yet understood. Stenens LC and Varnum DS,1974. 4 and Hiaro Y and Eppig JJ (1997) 5 postulated that teratomas were derived from oocytes that undergo maturation and spontaneous parthenogenic activation followed by embryonic development within the ovarian follicles. MCT is usually asymptomatic and doesn't have any specific symptoms. MCT can be associated with acute complications including torsion, rupture, infection or haemolytic anaemia 6. Malignant transformation occurs in 1% of cases 7.

A transabdominal or transvaginal ultrasound reveals a large hyperechoic mass with posterior shadow-cone because of the sebaceous and hair materials or a hypoechoic cyst if it contains only sebaceous material liquid. The bones and teeth appear hyperechoic 8. MCT are sometimes difficult to distinguish on ultrasound from hemorrhagic cysts, mucinous cystic neoplasm and endometriomas 9. In these cases, the magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) plays an important role in diagnosis. Cystic teratoma appears as a large pelvic monocular cyst with a solid nodule named Rokitansky protuberance attached to a thin wall and protrudes in the cyst lumen. Figure 2 Standard T1 weighted images with fat saturated T1 weighted images establish the diagnosis when the fat removed and the fluid-fat levels is also seen. The sebaceous component of cystic teratoma is hyper-intense on T1-weighted images Figure 4. Findings of calcifications are variable and difficult to detect. Figure 3 However, 7% of MCT don't contain any fat or calcifications 10. IV contrast gives a small nodule and wall cyst enhancement. The relationship between the teratoma and other anatomic pelvic structures can be well evaluated 11.

Figure 2(a, b, c, d).Surgical finding showing (a, b) left ovarian cystectomy. We visualize the cleavage plane between the pseudo-cyst wall of endometria and the healthy ovarian parenchyma. (c) Appearance of left remaining adenexa after cystectomy. (d) Ovarian parenchyma was preserved.

Figure 3(a, b).a, Gross findings of the endometrioma with brown internal surface. b, Mature cystic teratoma with fat tissue and hair.

However, a complex cystic appearance may be mistaken for malignancy in 1-2% of large tumours. In these instances, demonstrating fat and Rokitansky protuberance can aid in the diagnosis of MCT, but contrast material IV is not useful in the evaluation of the endometriomas and can't differentiate it from other benign or malignant neoplasms.

Despite the association between ovarian mature cystic teratoma and cystic endometrioma being uncommon, this possibility must be considered in the differential diagnosis of multiple ovarian tumors in the same ovary. The correct radiological diagnosis is of great value in planning treatment with the most favourable prognostic.

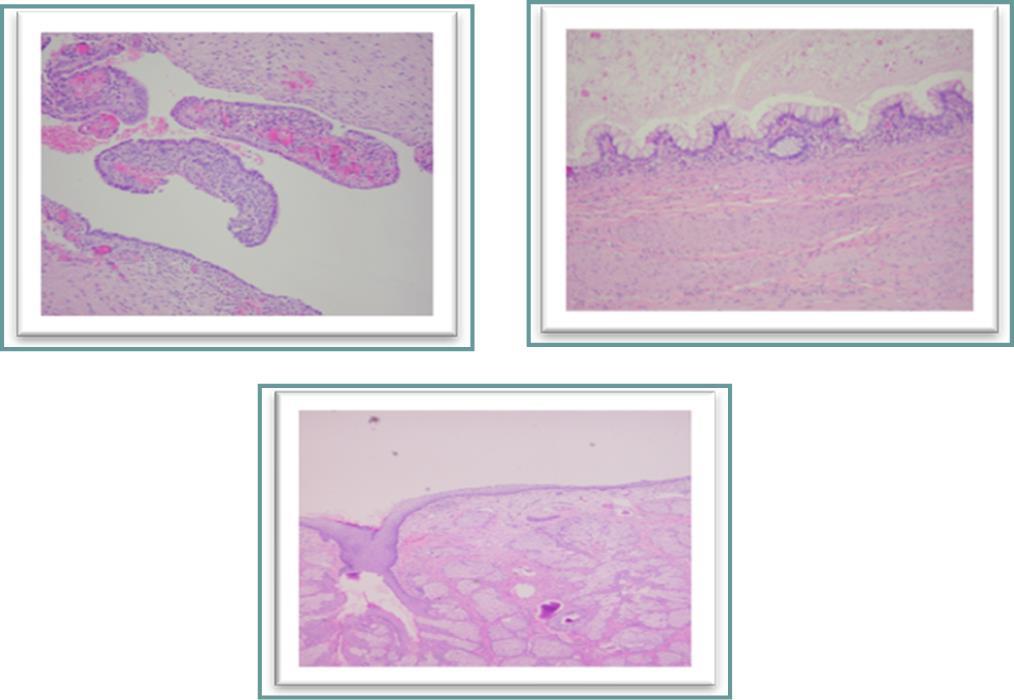

Figure 4(a, b, c).Histological examination. a, cyst lined by endometrial epithelium overcoming its endometrial stroma corresponding to an endometriosis cyst. b, a portion of the cystic mature teratoma lined with intestinal-type mucosa. c, skin surface-like structure with many sebaceous glands found on another part of the cyst.

Endometriosis is a complex pathology with various presentations affecting 10-15% of women of reproductive age and its physiopathology is still unclear. Several pathogenic theories are proposed: metastatic theory, metaplastic theory, induction theory, growth factors and immunity. It is defined as the presence of functional endometrial glands outside of the uterine cavity, ranging from microscopic implants to large cysts (endometrioma)12.The ovary is the first site of occurrence but endometrioma can appear in soft tissues, the gastrointestinal or urinary tracts and the chest 13. Clinically, endometriosis symptoms don't correlate with the severity and extension of the disease. Infertility, dyspareunia, dysmenorrhoea, and chronic pelvic pain are nonspecific for endometriosis. Ultrasound (US) shows a unilocular or multilocular structure with multiple separate cysts. Generally, the endometrioma is homogeneous, with a smooth echogenic wall, well-defined and has hypo-echoic content within the ovary. Endometrioma can have variable features sonographically and mimic other cystic ovarian neoplasms 14. MRI reveals a hyper-intense ovarian mass on T1-weighted that doesn't disappear in saturated fat and demonstrating a gradient of low signal intensity (shading) on T2-weighted images. Many endometrioma had shadows with varying degrees of signals of low to intermediate intensity according to the different stages of blood products present inside of the cyst. The differential diagnosis for ovarian endometriosis includes hemorrhagic cyst, mature cystic teratoma and mucinous cystic neoplasm. Figure 1Large masses with wall nodularities should be carefully sampled to rule out malignancy 15. The rarity of coexistence of teratoma with ovarian endomertioma adds to the difficulty to differentiate it from malignancy. This association constitutes a major diagnostic challenge radiologically, clinically and biologically, which ends in a treatment also challenging in itself. Since the first description of a possible link between endometriosis and ovarian cancer in 1925 by Sampson 16, many groups have investigated the association between malignant and benign tumours. Ottlenghi-Preti, Hennessy et al revealed a coexistence of a ovarian carcinoma with dermoid cyst 17, and Mareial Rojas and Ramiret De Arellano 18 revealed a coexistence of the malign melanoma with dermoid cyst. However, association between MCT and cystic endometrioma in the same ovary is extremely rare. Only few cases have been described in the English literature by E. Ferrario in 1960 19, Caruso et Pirrelli in 1997 20 and Frederick J and DaCosta V, in 2003 21.

Figure 1(a,b,c,d ).Two lesions within cystic component measuring 6 x 7 x 8 cm. MRI reveals a large and well-defined encapsulated tumour. Two solid components with an intermediate signal in T2 and T1 with a moderate contrast enhancement on T1 weighted.

This shows that there is still a lack of knowledge on the association between various types of tumours in the same ovary. Clinicians remain unable to diagnose simultaneous presence of two distinct pathologies in a single ovary. Moreover, it was reported that the level of serum CA-125 is often elevated in women with endometriomas and in cystic teratomas 22.

Despite advances in radiological technics, the coexistence of dual pathology tumour in the same ovary constitutes a major diagnostic challenge in radiology. The study of Benvancalster et al showed that ultrasound examiners assigned a correct specific diagnosis to at least 80% of endometriomas and 84% of dermoid cysts 22.

MRI characterizes with certainty the following benign injuries: cyst adenoma, serous, or fibrous tumors (Brenner tumor,fibroma and fibrothecoma),mature teratoma with fat as pathognomonic component and ovarian endometriomas 23.

However, a complex cystic appearance may be mistaken for malignancy in 1-2% of large tumours. In these instances, demonstrating fat and Rokitansky protuberance can aid in the diagnosis of MCT, but contrast material IV is not useful in the evaluation of the endometriomas and can't differentiate it from other benign or malignant neoplasms.

Despite the association between ovarian mature cystic teratoma and cystic endometrioma being uncommon, this possibility must be considered in the differential diagnosis of multiple ovarian tumors in the same ovary. The correct radiological diagnosis is of great value in planning treatment with the most favourable prognostic.

References

- 1.Comerci J T, JrLicciardi F, Bergh P A, Gregori C, Breen J L. (1994) Mature cystic teratoma: a clinicopathologic evaluation of 517 cases and review of the literature. Obstet Gynecol. 84, 22-28.

- 2.Rana S S, Swami N, Mehta S, Singh J, Biswal S.Intrapulmonary teratoma: an exceptional disease. , Ann Thorac Surg 2007, 1194-6.

- 3.Wu R T, Torng P L, Chang D Y. (1996) Mature cystic teratoma of the ovary: a clinicopathologic study of 283 cases. Zhonghua Yi Xue Za Zhi (Taipei),1996Oct. 58(4), 269-74.

- 4.Stenens L C, Varnum D S. (1974) The development of teratomas from parthenogenitically activated ovarian mouse eggs. , Dev Biol 37, 369-380.

- 5.Hiaro Y, Eppig J J. (1997) Parthenogenetic development of Mos-deficient mouse oocytes. , Mol Reprod Dev 48, 391-396.

- 6.Kimura I, Togashi K, Kawakami S, Takakura K, Mori T et al. (1994) Ovarian torsion: CT and MR imaging appearances. Radiology;190: 337-341.

- 7.Kido A, Togashi K, Konishi I. (1999) Dermoid cysts of the ovary with malignant transformation: MR appearance. , AJR Am J Roentgenol; 172, 445-449.

- 8.Smorgick N, Maymon R. (2014) Assessment of adnexal masses using ultrasound: a practical review. , J Womens Health,2014Sep23; 6, 857-63.

- 9.Patel M D, Feldstein V A, Lipson S D, Chen D C, Filly R A. (1998) Cystic teratomas of the ovary: diagnostic value of sonography. , AJR Am J Roentgenol 171-1061.

- 10.Outwater E K, Siegelman E S, Hunt J L. (2001) Ovarian teratomas: tumor types and imaging characteristics. RadioGraphics. 21, 475-490.

- 11.Guinet C, Ghossain M A, Buy J N. (1995) . Mature cystic teratomas of the ovary: CT and MR findings. Eur J Radiol 20, 137-143.

- 12.Gazvani R, Templeton.A (2002) New considerations for the pathogenesis of endometriosis. , Int J Gynecol Obstet 76(2), 117-126.

- 13.Channabasavaiah A D, Joseph J V. (2010) Thoracic endometriosis: revisiting the association between clinical presentation and thoracic pathology based on thoracoscopic findings in 110 patients. , Medicine (Baltimore)May; 89(3), 183-8.

- 14.Woodward P J, Sohaey R, Mezzetti T P.Endometriosis: radiologic-pathologic correlation. , Radiographics 21(1), 193-216.

- 15.Ha H K, Lim Y T, Kim HS et-al. (1994) Diagnosis of pelvic endometriosis: fat-suppressed T1-weighted vs conventional MR images. , AJR Am J Roentgenol; 163(1), 127-31.

- 16.Sampson J A. (1925) Endometrial carcinoma of the ovary, arising in endometrial tissue in that organ. , Arch Surg 10, 1.

- 17.Ottolenghi-Preti G F. (1960) Bilateral dermoid cysts of the ovary in pregnancy (presentation of 2 cases). , Quad Clin Ostet Ginecol 15, 162-190.

- 18.Marcial-Rojas R A, GA Ramirez de Arellano. (1956) Malignant melanoma arising in a dermoid cyst of the ovary. Report of a case. Cancer. 9, 523-7.

- 19.FERRARIO E.Association of ovarian endometriosiand dermoid cyst. Minerva ginecologica 1960;12:. 570-2.

- 20.Caruso M L, Pireli M. (1997) A rare association between endometriosis and bilateral ovarian teratoma. A case report.Minerva Ginecol. 49, 341-3.

- 21.Frederick J. (2003) Périodique : The West Indian medical journal .Volume. 52 ,N° : 2 ,Pages : 179-81 Année : .