Potential use of Ginger (Zinger officinale Rose) Extracts as Biopesticide against Myzuspersicae Sulzer (Hemiptera, Aphididae) on Pepper Crops

Abstract

Chemical insecticides have been the primary method used by farmers to control pests. However, their negative environmental impacts, harmful effects on beneficial insects and human health, and prohibition in organic farming systems have driven the search for natural alternatives with insecticidal properties. These alternatives provide a safer and more sustainable way to control insect pests. Medicinal plants and their constituents play an important role in pest management. For example, ginger (Zingiber officinale) extracts contain bioactive compounds with insecticidal activities. The objective of this work was to track the population of the green peach aphid (Myzuspersicae) on pepper crops in a greenhouse, identify the active ingredients in ginger extracts, and evaluate the insecticidal effects of three concentrations of ginger-derived aqueous and essential oil extracts against M. persicae on pepper plants under laboratory and greenhouse conditions. The results demonstrate that M. persicae grows rapidly on pepper crops under greenhouse conditions, reaching high densities on leaves. The ginger extract contains two active ingredients with insecticidal effects against this pest. The significant reduction in aphid (M. persicae) populations indicates that Z. officinale aqueous extract (150 mL/L) and essential oil (2 mL/L) have strong potential for the biological control of this pest under greenhouse conditions. Thus, the use of ginger plant extract emerges as a promising alternative for reducing M. persicae infestations on pepper plants.

Author Contributions

Copyright © 2025 Mdellel Lassaad, et al.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Competing interests

The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

Citation:

Introduction

In Saudi Arabia, in recent years, sweet pepper (Capsicum annuum L.) has been one of the three major commercial vegetable crops grown alongside tomato and cucumber. It is a widely consumed crop due to its pleasant flavor and beneficial effects on human health 1, 2. During its growth period, from the seedling stage to maturity, sweet pepper is attacked by numerous pests that reduce both the quantity and quality of production. The Western flower thrips (Frankliniella occidentalis (Pergande)), the whitefly (Bemisiatabaci (Genn.)), the two-spotted spider mite (Tetranychusurticae (Koch)), the cotton aphid (Aphis gossypii (Glover)), and the green peach aphid (Myzuspersicae (Sulzer)) are the five major pest species that damage different parts of the pepper plant and limit production 3, 4. Among these, M. persicae causes extensive damage to pepper plants, including wilting, defoliation, and flower and fruit abortion 5. When feeding on pepper, M. persicae produces honeydew, which can affect fruit quality and reduce photosynthetic capacity by promoting mold growth6. However, the most serious damage occurs indirectly through the transmission of viruses such as Potato Virus Y (PVY), Pepper mild mottle virus (PMMoV), and Pepper yellow mosaic virus (PepYMV)7. These significant damages pressure farmers into excessive use of chemical insecticides. The uncontrolled application of such chemicals has led to environmental contamination, pesticide resistance, pest resurgence, and negative impacts on pollinators and beneficial insects 8, 9. To address these issues, there is a growing need for farmers and consumers to adopt alternative, sustainable methods for controlling M. persicae. Insect predators, parasitoids, and biopesticides derived from natural sources (such as bacteria, plants, and animals) are considered sustainable alternatives to chemical insecticides10. Among biopesticides, plant-derived formulations represent a small but important group, offering advantages such as reduced risk of resistance (due to multiple bioactive compounds), low environmental persistence, and cost-effectiveness 11, 12, 13.These plant-based pesticides can act through various mechanisms, including repelling or attracting insects, inhibiting feeding, disrupting respiration, interfering with host plant identification, reducing oviposition, and impairing adult emergence via ovicidal and larvicidal effects13, 14, 15, 16. The insecticidal effects of plant extracts (aqueous extracts or essential oils) against aphids, particularly M. persicae, have been documented in several studies. For instance, aqueous extracts of pot marigold (Calendula officinalis Linn.), mint (Mentha viridis Linn.), and rosemary (Salvia rosmarinus Spenn.) have been shown to reduce M. persicae populations on pepper crops 6. Similarly, Gouvea et al. 17 demonstrated that foliar application of ethanol extracts from paracress (Acmella oleracea Linn.) resulted in 90% mortality of M. persicae and reduced its fecundity.

Ginger (Zingiber officinale Roscoe, Zingiberaceae) is the root of a flowering plant that has long been used as both a spice and an herbal medicine18. It is employed to alleviate and treat various common ailments, such as headaches, colds, nausea, and vomiting. Many bioactive compounds in ginger, including phenolic and terpene compounds, have been identified19. However, to our knowledge, the insecticidal effects of these bioactive compounds have not yet been studied. Additionally, there is no research on the active ingredients in ginger or their impact on M. persicae populations, plant growth, or production quality.

For this, this study aims to: (1) Identify the active ingredients in ginger extracts and (2) Evaluate the insecticidal effects of three concentrations of ginger aqueous and essential oil extracts against M. persicaeon pepper plants under laboratory and greenhouse conditions.

Materials and Methods

From September 2023 to August 2024, a randomized complete block design with three replications and nine treatments was conducted in a controlled greenhouse and laboratory at the National Organic Agriculture Center in Unaizah/Al-Qassim, Saudi Arabia (26.085478°N, 43.9768123°E). The nine treatments consisted of: (1) Foliar application of three concentrations of ginger essential oil (GEO): CGEO1: 1 mL/L, CGEO2: 1.5 mL/L, and CGEO3: 2 mL/L, (2) Foliar application of three concentrations of ginger aqueous extract (GAE): CGAE1: 50 mL/L, CGAE2: 100 mL/L, CGAE3: 150 mL/L, (3) Aphi-Killer (a biopesticide; active ingredient: Pyrethrin 1.5% EW, specific for aphid control; dose: 1 mL/L), (4) Dominate (a chemical pesticide; active ingredient: Abamectin 1.8% W/V, specific for mite and insect control; dose: 0.5 mL/L) and (5) Water (control treatment).

Experimental Design and Planting

In the greenhouse, which measured 40 meters in length and 9 meters in width, organic fertilizer (vermicompost) was added at a rate of 10 tons per hectare. The soil was then divided into six ridges, each 36 meters long, with each ridge further divided into five blocks separated by 1-meter gaps. A total of 27 blocks were used in the experiment, with each block containing four plants. Under a drip irrigation system, pepper (Capsicum annuum L.) seedlings of the 'Shakira' variety were transplanted 50 cm apart on 15 November 2023. From transplanting to the fruiting period, ©Neutrals (4-12-5; 7-5-4; 5-5-14) was applied weekly as a mineral fertilizer at recommended doses via the fertigation system, while the greenhouse temperature was maintained at 24±1°C.

In the laboratory, under controlled conditions of 25±1°C and 60±10% relative humidity, a total of 108 sweet pepper plants of the 'Shakira' variety were planted on 15 November 2023 in 30-cm-diameter plastic pots filled with a mixture of two parts peat moss and one-part sand. The plants were watered every three days and divided into 27 groups, each consisting of four plants. At the 8-leaf stage, each pepper plant was artificially infested with four adult apterous M. persicae, collected from infested pepper plants in the greenhouse.

Plant Growth and Aphid Population Survey in the Greenhouse

During the period from 15 November 2023 to 03 March 2024, the plants used in the experiment were monitored, and the number of leaves per plant, the number of infested plants, the number of infested leaves per plant, and the number of wingless adult morphs of M. persicae per leaf were recorded weekly. The mean relative growth rate (MRGR = F₁) and the generation time (T = F₂) of M. persicae were then calculated using the formulas described by Leather and Dixon20 and Ramade 21:

F₁ (MRGR) = (ln N(Dₙ) – ln N(Dₙ₋₁)) / (Dₙ – Dₙ₋₁)

F₂ (T) = log2 / MRGR

where: N(Dₙ) = number of M. persicae per leaf on date *n*, N(Dₙ₋₁) = number of M. persicae per leaf on the previous date (*n-1*), and D = date of counting.

Preparation of Ginger Extracts and Determination of Active Ingredients

The fresh rhizomes of ginger (Zingiber officinale Rose) procured from the local market were washed with water and dried for 15 days according to the method of Sarwar 22. The dried rhizomes were ground and used to prepare an aqueous ginger extract following the method of Mdellel et al. 6. Ginger essential oils were extracted using the hydro-distillation method with a Clevenger apparatus. A quantity of 100 g of fresh ginger rhizomes was placed in a 1000 mL glass flask, to which 600 mL of distilled water was added until the entire sample was fully immersed 23. For the determination of ginger's active ingredients, the rhizomes were soaked in a 1:1 water-to-ethanol solution for 24 hours at the Central Laboratory of the National Organic Agriculture Center. The mixture was then placed on a vibrator for 2 hours and filtered using 125-micron filter paper to remove impurities and plant tissue. Afterward, 100 mL of diethyl ether was added, and the samples were dried using anhydrous sodium sulfate. Next, 10 mL of acetonitrile was used to dissolve the active ingredients, which were then analyzed using a GC-MSMS-TSQ9610 Mass Spectrometer, following the method of Abubakar and Haque 24.

Experiment Execution and Recorded Data

In both the greenhouse and laboratory, four infested leaves from each plant were selected and marked. The total number of immature and mature stages of M. persicae on each selected leaf was recorded one hour before treatment application. Additionally, the number of wingless morphs of M. persicae on each marked leaf was counted one hour before treatment and at 24, 48, 72, 96, 120, and 144 hours after spraying. Foliar application of all treatments in the laboratory and greenhouse was conducted on April 3, 2024, depending on your date format). During treatment, a distance of approximately 40 cm between the nozzle and the plant shoots was maintained. The insecticidal effect of different concentrations of aqueous ginger extract, ginger essential oil, the biopesticide (Aphikiller), the chemical insecticide (Dominate), and the control on M. persicae on pepper plants was evaluated in both the laboratory and greenhouse. This was determined by calculating the population reduction rate of M. persicae and the corrected efficacy percentage. The reduction rate was calculated using the formula by Mdellel et al. 6:

Reduction rate (%) = [(Pretreatment average number of M. persicae – Average number of M. persicae after treatment)/ Pretreatment average number of M. persicae] × 100.

The corrected efficacy was calculated according to Henderson and Tilton 25 formula:

Correct efficacy (%) = [1 – (N in Co before treatment * N in T after treatment / N in Co after treatment * N in T before treatment) * 100.

Where: N = Number of immature and mature apterous stages of M. persicae per selected leaf, Co = Control plants, and T = Treatment.

Statistical analysis

The data were statistically analyzed through the one-way analysis of variance (AVOVA) using SPSS26. software program version 23. The statistical significance was considered as * if p<0.05, ** if p < 0.01, and *** if p<0.001, and ns-not significant. The statistical analysis was done using Duncan's Multiple Range Test (DMRT) at p<0.05.

Results

Plant Growth and Aphid Population Survey

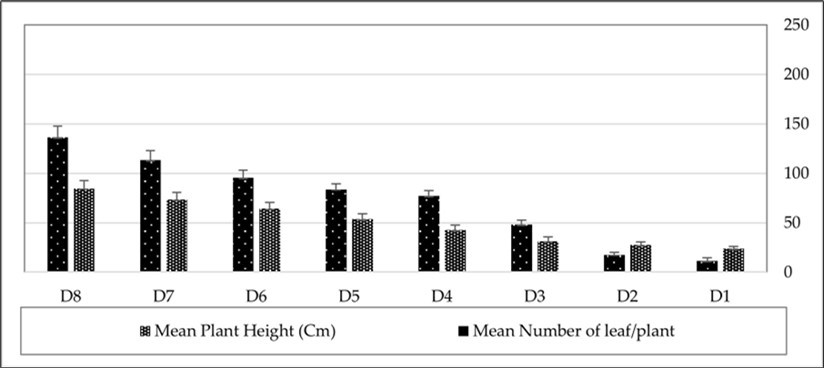

The survey of pepper plant growth in the greenhouse during the November 2023 – March 2024 period demonstrated that the height of the plants increased from 23.66 ± 2.24 cm at the first measurement (one week after planting) to 84.66 ± 7.33 cm by early March 2024. Similarly, the mean number of leaves per plant increased, reaching 136.33 ± 11.42 leaves per plant (Figure 1).

Figure 1.Pepper plant height and number of leaves per plant during November 2023 – March 2024 period.

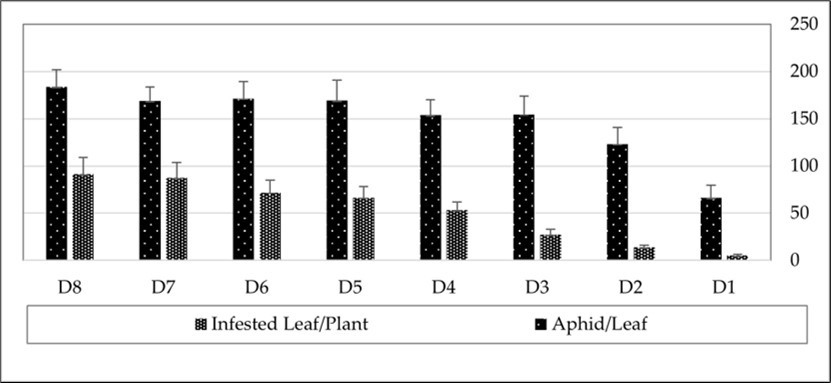

The survey of pepper plants in the greenhouse showed the first observation of M. persicae on growing leaves in mid-December 2023. The average number of infested leaves increased from 5.24 leaves per plant in early January to 91.4 leaves per plant by March 2024 (Figure 2). Monitoring of M. persicae on pepper plants in the greenhouse from January to March 2024 demonstrated that the aphid population grew rapidly, reaching 183.66 aphids per leaf by early March 2024 (Figure 1). The mean relative growth rate of the aphid was 0.071 ± 0.009, and the generation time was 9.71 ± 0.83 days.

Figure 2.The number of infested leaves per plant and the average number of Myzus persicae per leaf in a greenhouse-grown pepper crop.

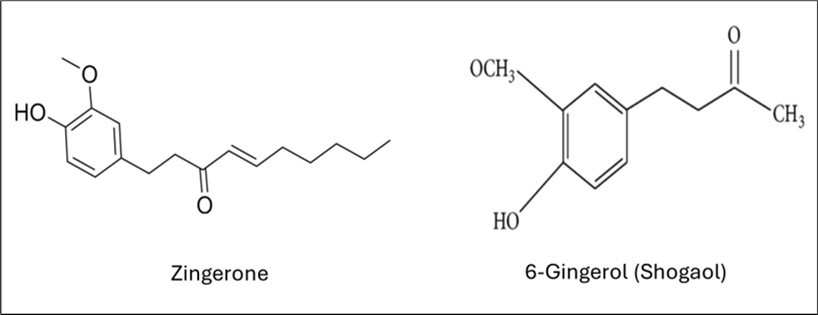

Active Ingredients

The GC-MS analysis of ginger (Zingiber officinale) rhizome extracts, conducted using an MS-TSQ9610 Mass Spectrometer system, identified two active ingredients: zingerone and 6-gingerol (shogaol). The chemical structures of zingerone and 6-shogaol were presented in Figure 3.

Figure 3.Structures of the active ingredients (zingerone and 6-gingerol) identified in ginger rhizome extracts.

The chemical formula and molecular weight of each identified active ingredient were presented in Table 1.

Table 1. Chemical formula and molecular weight of zingerone and 6-Gingerol| Active Ingredient Name | Molecular Formula | Molecular Weight (g/mol) |

|---|---|---|

| Zingerone | C11H14O3 | 194.23 g/mol |

| 6-Gingerol | C17H24O3 | 276.37g/mol |

Efficacy of Ginger Aqueous Extract in Controlling M. persicae under Laboratory and Greenhouse Conditions

The data presented in Table 2 show the reduction rate of M. persicae populations on pepper leaves and the corrected efficacy (%) 144 hours after foliar application for all treatments under laboratory and greenhouse conditions.

Table 2. Reduction rate and Correct efficacy of treatments against Myzus persicae populations on pepper plants in laboratory and greenhouse conditions.| Treatments | Laboratory | Greenhouse | ||

| Reduction rate(%) | Correct Efficacy (%) | Reduction Rate (%) | Correct Efficacy (%) | |

| CGAE1(50 mL/L) | 38.02±3.36e | 37.89±2.79e | 34.68±3.05c | 31.87±2.79c |

| CGAE2(100 mL/L) | 41.09±2.86d | 40.14±2.82d | 40.44±4.45b | 37.66±4.86b |

| CGAE3(150 mL/L) | 44.74±4.79c | 43.37±4.44c | 42.24±5.54b | 39.63±5.29b |

| Aphikiller | 48.88±4.75b | 47.58±4.62b | 43.12±5.24b | 40.61±5.08b |

| Dominate | 68.22±4.19a | 67.80±2.53a | 54.95±6.31a | 52.97±6.22a |

| Control | 2.56±0.77f | 0±0 | 4.37±1.76d | 0±0 |

| significance | *** | *** | *** | *** |

In the laboratory, the reduction rate ranged between 38.02 ± 3.36% and 68.22 ± 4.19%. The highest reduction rate (68.22 ± 4.19%) was observed with the chemical treatment. The use of ginger aqueous extract concentrations significantly reduced the M. persicae population compared to the control. The lowest reduction rate (38.02 ± 3.36%) and corrected efficacy (37.89 ± 2.79%) were recorded after the application of CGAE1 (50 mL/L), while the highest reduction rate (44.74 ± 4.79%) and corrected efficacy (39.63 ± 5.29%) were observed after the application of CGAE3 (150 mL/L). Significant differences (p ≤ 0.001) in the reduction rate and corrected efficacy were observed after the foliar application of CGAE1, CGAE2, and CGAE3 compared to the control treatments. However, there was no significant difference in the reduction rate and corrected efficacy between the biopesticide (Aphikiller) and CGAE3.

In the greenhouse, the reduction rate ranged between 34.68 ± 3.05% and 54.95 ± 6.31%. The highest reduction rate (54.95 ± 6.31%) was recorded after the application of the chemical pesticide. The results in Table 2 indicate that foliar application of ginger aqueous extract reduced the M. persicae population, with reduction rates ranging from 34.68 ± 3.05% to 42.24 ± 5.54%, depending on the applied concentration. The corrected efficacy, also dependent on the applied concentration, ranged between 31.87 ± 2.79% and 39.63 ± 5.29%. Spraying ginger aqueous extract at concentration CGAE3 (150 mL/L) resulted in the highest reduction rate (42.24 ± 5.54%) and a corrected efficacy of 40.61 ± 5.08%, compared to CGAE2, CGAE1, and the control. Significant differences (p ≤ 0.001) in reduction rate and corrected efficacy were observed after foliar application of CGAE1, CGAE2, and CGAE3 compared to the control treatments. However, spraying ginger aqueous extract at CGAE3 (150 mL/L) and the biopesticide Aphikiller yielded roughly similar results in terms of reduction rate and corrected efficacy.

Ginger essential oil efficiency to Control M. persicae in laboratory and greenhouse Conditions

The reduction rates and corrected efficacy of treatments with three concentrations of ginger essential oil (GEO), Aphikiller, Dominate, and the control on the population of M. persicae on pepper plants in laboratory and greenhouse conditions are presented in Table 3.

Table 3. Reduction rate and Correct efficacy of treatments against Myzus persicae populations on pepper plants in laboratory and greenhouse conditions.| Treatments | Laboratory | Greenhouse | ||

| Reduction rate(%) | CorrectEfficacy (%) | Reduction Rate (%) | CorrectEfficacy (%) | |

| CGEO1(1 mL/L) | 40.73±3.57d | 39.90±3.15d | 38.45±3.36d | 35.64±2.73d |

| CGEO2(1.5 mL/L) | 43.58±3.41c | 42.62±3.76c | 40.58±4.13c | 37.87±2.44c |

| CGEO3(2 mL/L) | 45.80±4.43b | 44.33±2.90b | 42.49±5.71b | 39.95±4.61b |

| Aphikiller | 46.67±3.73b | 45.62±3.96b | 43.12±5.24b | 40.62±5.08b |

| Dominate | 68.22±4.19a | 67.16±4.62a | 54.95±6.31a | 52.97±6.22a |

| Control | 2.56±0.88e | 0±0 | 4.37±1.76e | 0±0e |

| significance | *** | *** | *** | *** |

In the laboratory, the reduction rate ranged between 40.73 ± 3.57% and 68.22 ± 4.19%. The highest reduction rate (68.22 ± 4.19%) was observed with the chemical treatment. The use of ginger essential oil concentrations significantly reduced the M. persicae population compared to the control. The lowest reduction rate (40.73 ± 3.57%) and corrected efficacy (39.90 ± 3.15%) were recorded after the application of CGEO1 (1 mL/L), while the highest reduction rate (45.80 ± 4.43%) and corrected efficacy (44.33 ± 2.90%) were observed after the application of CGEO3 (2 mL/L). Significant differences (p ≤ 0.001) in the reduction rate and corrected efficacy were observed after the foliar application of CGEO1, CGEO2, and CGEO3 compared to the control treatments. However, there was no significant difference in the reduction rate and corrected efficacy between the biopesticide (Aphikiller) and CGEO3.

In the greenhouse, the reduction rate ranged between 38.45 ± 3.36% and 54.95 ± 6.31%. The highest reduction rate (54.95 ± 6.31%) was recorded after the application of the chemical pesticide. The results in Table 3 indicate that foliar application of ginger essential oil reduced the M. persicae population, with reduction rates ranging from 38.45 ± 3.36% to 42.49 ± 5.71%, depending on the applied concentration. The corrected efficacy, also dependent on the applied concentration, ranged between 35.64 ± 2.73% and 39.95 ± 4.61%. Spraying ginger essential oil at concentration CGEO3 (2 mL/L) resulted in the highest reduction rate (42.49 ± 5.71%) and a corrected efficacy of 39.95 ± 4.61%, compared to CGEO2, CGEO1, and the control. Significant differences (p ≤ 0.001) in reduction rate andcorrected efficacywere observed after foliar application of CGEO1, CGEO2, and CGEO3 compared to the control treatments. However, spraying ginger essential oil at CGEO3 (2 mL/L) and the biopesticide Aphikiller yielded roughly similar results in terms of reduction rate and corrected efficacy.

Discussion

In this study, we aimed to determine specific life table parameters of the green peach aphid (Myzuspersicae) in greenhouse conditions, identify the active ingredients in ginger extracts, and evaluate the insecticidal effects of three concentrations of aqueous ginger extract and ginger essential oil against M. persicae on pepper plants under both laboratory and greenhouse conditions.

Regarding the specific life table parameters of the green peach aphid (M. persicae), research indicates that it grows rapidly on host plants in greenhouse environments. Its physiological functions—such as locomotion, feeding, and population fitness—are significantly influenced by host plant species and environmental factors, particularly temperature and humidity 27, 28, 29.

In our experiment, we observed rapid population growth of M. persicae on pepper plants under greenhouse conditions, resulting in complete infestation, short generation times (9.71 ± 0.83 days), and high aphid density per leaf (183.66 aphids/leaf). These findings align with reports by Ali et al. 28 and Mdellel et al. 6who demonstrated that at 25°C, M. persicae on pepper plants develops rapidly, with a mean relative growth rate (MRGR) between 0.048 and 0.068 and a generation time of 10.29 days. These biological parameters explain the high infestation density observed per pepper leaf in our study. The short development period and high fecundity of M. persicae make this species particularly difficult to control. Several studies have emphasized the importance of understanding aphid biological parameters to develop optimal control strategies 30. Since, aphid life cycles depend on multiple factors—including host plant characteristics, temperature, and humidity—the selection of control methods should carefully consider how these factors influence treatment efficacy 13.

Currently, the phytosanitary management of the green peach aphid in pepper crops relies primarily on the intensive application of chemical insecticides to reduce pest populations. However, their indiscriminate use leads to problems such as negative environmental impacts, harm to beneficial insects, and risks to human health 8, 9. Additionally, consumers are increasingly concerned about pest management in crops, making the pursuit of more sustainable production strategies essential. Therefore, Integrated Pest Management (IPM) emerged in response to the excessive use of pesticides, aiming to limit their impact. It combines various management strategies in an economical and environmentally sustainable way, reducing farmers' exposure to insecticides and lowering toxic residue levels in vegetables 31. Within the IPM, the use of plant extracts serves as an important control strategy, offering favorable toxicological properties due to their content of bioactive ingredients. These bioactive ingredients exhibit multiple modes of action against insects, including antifeedant and repellent effects, fecundity reduction, respiration inhibition, cuticle disruption, and neurotoxicity 32.

Regarding ginger, our results demonstrate that it contains two bioactive compounds—zingerone and 6-gingerol (shogaol)—which negatively affect M. persicae populations on pepper plants under greenhouse conditions. The presence of zingerone and shogaol as bioactive compounds in ginger extracts has been reported in several studies 19, 33. The insecticidal effects of these compounds have been documented against various pests. For instance, Agarwal et al. 34 showed that shogaol in ginger influences insect metabolic processes, including chitin synthesis, respiratory and central nervous systems, sexual communication, larval shrinkage, and ultimately, insect death. Future studies should investigate: (1) the specific modes of action of these two compounds (zingerone and 6-gingerol) against M. persicae, and (2) their potential effects on key natural enemies such as the seven-spot ladybird beetle (Coccinella septempunctata L.; Coleoptera: Coccinellidae), the parasitoid wasp Aphidiuscolemani Viereck (Hymenoptera: Braconidae) and larva stage of the green lacewing Chrysoperlacarnea Stephens (Neuroptera: Chrysopidae).

In this study, our results demonstrated that both ginger aqueous extract and ginger essential oil exhibited toxicity against M. persicae under greenhouse and laboratory conditions, with efficacy varying by concentration. The highest doses (CGAE3: 150 mL/L aqueous extract and CGEO3: 2 mL/L essential oil) showed the strongest insecticidal effects, achieving corrected efficacy rates of 43.37 ± 4.44% and 44.33 ± 2.90%, respectively, in the laboratory, and 39.63 ± 5.29% and 39.95 ± 4.61%, respectively, in the greenhouse. The insecticidal effect of ginger extracts has been demonstrated in several studies. Ogbonna et al. 33 reported the insecticidal activity of ginger against Prostephanus truncatus Horn (Coleoptera: Bostrichidae) infesting maize. Similarly, Hamada et al. 35 documented the insecticidal activity of ginger oils against the cotton leafworm, Spodoptera littoralis (Boisd.) (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae). Abdulhay et al. 36also confirmed their efficacy against the black bean aphid (Aphis fabae Scop.).

In terms of efficacy, our results showed that the reduction rate and corrected efficacy were around 40% in both laboratory and greenhouse conditions, demonstrating comparable efficacy to the commercial biopesticide Aphikiller and approaching the performance of chemical insecticides. Our findings align with those of Farouk et al. 37, who demonstrated that jasmine essential oils at a concentration of 2.5 mL/L reduced the red spider mite (Tetranychusurticae) population on eggplant by 49.03% in the greenhouse. Similarly, Mdellel et al. 6 reported that the efficacy of aqueous extracts from mint (Mentha viridis), marigold (Calendula officinalis), and rosemary (Salvia rosmarinus) against M. persicae on pepper plants increased with concentration, ranging between 32% and 61% in laboratory tests. Likewise, Ahmed et al. 38 observed higher mortality rates in M. persicae populations with increasing concentrations of essential oils from black pepper (Piper nigrum), eucalyptus (Eucalyptus globulus), and rosemary (Salvia rosmarinus).

These results are particularly encouraging for organic and sustainable farmers, who often struggle to find effective, environmentally safe solutions to manage pests like Myzuspersicae. The promising performance of ginger extracts—especially at higher concentrations—suggests they could become a valuable component of integrated pest management (IPM) strategies in greenhouse pepper cultivation. Moving forward, further research is needed to test these extracts under real farming conditions, assess their scalability and ease of application, and evaluate their cost-effectiveness and practicality for growers. This should include examining their impact on additional pepper fruit components, such as nitrogen, phosphorus, protein, phenols, and antioxidants. Subsequent studies should also investigate residue levels and establish safety intervals following ginger extracts applications against M. persicae on peppers and other vegetable crops.

To align these results with comprehensive IPM approaches, additional research comparing them to alternative botanical insecticides, along with in-depth residue testing, is necessary to ensure food safety and regulatory adherence.

Conclusions

This study demonstrates that M. persicae grows rapidly on pepper crops under greenhouse conditions, reaching high densities on leaves. The ginger Zingiber officinale extract contains two active ingredients with insecticidal effects against this pest. The significant reduction in aphid (M. persicae) populations indicates that Z. officinale aqueous extract (150 mL/L) and essential oil (2 mL/L) have strong potential for the biological control of this pest under greenhouse conditions. However, additional research is needed to: (1) elucidate the exact mode of action of Z. officinale extracts against M. persicae, (2) evaluate their effects on natural enemies and pollinator insects, (3) assess their impact on plant growth and production, and (4) determine their effect on fruit nutrient content.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the Ministry of Environment, Water, and Agriculture (Saudi Arabia), the Organic Farming Administration, and the Saudi Organic Farming Association for overseeing and funding the current work through the Scientific Research Development Project in Organic Farming (Grant No. 550324124684). The authors also acknowledge the Central Laboratory of the National Organic Agriculture Center for chemical analysis and the National Center for Sustainable Agriculture Research and Development (Estidama) for overseeing the research project.

Abbreviations

References

- 1.Brezeanu C, Brezeanu P M, Stoleru V, Irimia L M, Lipsa F D et al. (2003) . Nutritional Value of New Sweet Pepper Genotypes Grown in Organic System.Agriculture12, 1863. https://doi.org/10.3390/ agriculture12111863 .

- 2.Kumar R, Kumari P, Kumar S. (2016) Effect of irrigation levels and frequencies on yield, quality and water use efficiency of capsicum grown under protected conditions.Int. , J. Bio-res. Stress Manage7 6, 1290-1296.

- 3.Arnaouty S A El, A H El-Heneidy, Afifi A I. (2020) Comparative study between biological and chemical control programs of certain sweet pepper pests in greenhouses.Egypt. , J Biol Pest Control30 28-10.

- 4.Mdellel L, Adouani R, Halima K M Ben. (2019) Influence of compost fertilization on the biology and morphology of green peach aphid (Myzus persicae) on pepper.Int. , J. Policy. Res7 48-54.

- 5.Sun M, R E Voorrips, Steenhuis-Broers G. (2018) Reduced phloem uptake ofMyzuspersicaeon an aphid resistant pepper accession.BMC Plant Biol18. 10-1186.

- 6.Mdellel L, Abdelli A, Omar K, El-Bassam W, Al-Khateeb M. (2021) Effect of aqueous extracts of three different plants onMyzuspersicaeSulzer (Hemiptera: Aphididae) infesting pepper plants under laboratory conditions.Eur. , J. Environ. Sci11 101-106.

- 7.Kenyon L, Kumar S, W S Tsai, J D Hughes. (2014) Virus diseases of peppers (Capsicum spp.) and their control.Adv. Virus Res90 297-354.

- 8.Rundlöf M, G K Andersson, Bommarco R, Fries I, Hederström V et al. (2015) Seed coating with a neonicotinoid insecticide negatively affects wild bees.Nature521. , H G Smith 77-80.

- 9.S G Potts, Imperatriz-Fonseca V, H T Ngo. (2016) Safeguarding pollinators and their values to human well-being.Nature540. , M A Aizen, J C Biesmeijer, T D Breeze, L V Dicks, L A Garibaldi, R Hill, J Settele, A J Vanbergen 220-229.

- 10.Kumar J, Ramlal A, Mallick D, Mishra V. (2021) An overview of some biopesticides and their importance in plant protection for commercial acceptance.Plan. Theory10: 1185. doi: 10.3390/plants10061185. [PubMed]

- 11.Angioni A, Dedola F, Minelli E V, Barra A, Cabras P et al. (2005) Residues and half-life times of pyrethrins on peaches after field treatments. , J. Agric. Food. Chem18;53 4059-63.

- 12.Caboni P, Sarais G, Angioni A, Garcia A J, Lai F et al. (2006) Residues and persistence of neem formulations on strawberry after field treatment.J. , Agric. Food Chem54 10026-10032.

- 13.Khursheed A, M A Rather, Jain V, A R Wani, Rasool S et al. (2022) Plant based natural products as potential ecofriendly and safer biopesticides: A comprehensive overview of their advantages over conventional pesticides, limitations and regulatory aspects.Microb.Pathog173. 105854-10.

- 14.Tripathi A, Upadhyay S, Bhuiyan M, P A Bhattacharya. (2009) review on prospects of essential oils as biopesticide. in insect-pest management.Pharmacog. Phytotherap1, 052-063. doi: 10.5897/JPP.9000003 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Halder J, Rai A B, Kodandaram M H. (2013) . Compatibility of Neem Oil and Different Entomopathogens for the Management of Major Vegetable Sucking Pests.Natl. Acad. Sci. Lett36 [CrossRef] .

- 16.Ali H, Islam S, Sabiha S, S B Rekha, Nesa M et al. (2017) Lethal action ofArgemone mexicanaL. extracts againstCulexquinquefasciatusSay larvae andTriboliumcastaneum(Hbst.) adults.J.Pharmacogn.Phytochem6. 438-441.

- 17.S C Gouvêa, Geraldo F, Elisangela R, Arthur F, E P Marcelo. (2019) Effects of paracress (Acmellaoleracea) extracts on the aphidsMyzuspersicaeandLipaphiserysimiand two natural enemies.Ind. Crops Prod128 399-404.

- 18.Y A Han, C W Song, W S Koh, G H Yon, Y S Kim et al. (2013) . Anti-inflammatory effects of the Zingiber officinale Roscoe constituent 12-dehydrogingerdione in lipopolysaccharide-stimulated raw 264.7 cells.Phytother. Res27, 1200–1205. doi: 10.1002/ptr.4847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] .

- 19.Q, X Y, S Y Cao, R Y Gan, Corke H et al. (2019) . Bioactive Compounds and Bioactivities of Ginger (Zingiber officinaleRoscoe).Foods30,8(6), 185. doi: 10.3390/foods8060185. PMID: 31151279; PMCID: PMC6616534 , H B Li.

- 20.S R Leather. (1984) Aphid growth and reproductive rate.Entomol.Expn. Appl35 , A F G Dixon 137-140.

- 22.Sarwar M. (2015) The killer chemicals for control of agriculture insect pests: the botanical insecticides.Int. , J. Cheam.Biomol. Sci1 123-128.

- 24.A R, Haque M. (2020) Preparation of Medicinal Plants: Basic Extraction and Fractionation Procedures for Experimental Purposes.J. , Pharm.Bioallied 12(1), 1-10.

- 25.C F Henderson. (1955) Tests with acaricides against the brow wheat mite.J. Econ.Entomol48 , E W Tilton 157-161.

- 27.Chen W, Zhao D, He Y. (2022) . Different Host Plants Distinctly Influence the Adaptability ofMyzuspersicae(Hemiptera: Aphididae).Agriculture12 .

- 28.M Y Ali, Naseem T, Arshad M, Ashraf I, Rizwan M et al. (2021) . Host-Plant Variations Affect the Biotic Potential, Survival, and Population Projection ofMyzuspersicae(Hemiptera: Aphididae).Insects21;12(5), 375. doi: 10.3390/insects12050375. PMID: 33919340; PMCID: PMC8143353 .

- 29.S Y Wang, B L Wang, G L Yan, Y H Liu, D Y Zhang. (2020) Temperature-Dependent Demographic Characteristics and Control Potential ofAphelinusasychisReared fromSitobionavenaeas a Biological Control Agent for Myzus persicae on Chili Peppers.Insects11. , T.X Liu 475-10.

- 30.Ali J, Bayram A, Mukarram M, Zhou F, M F Karim. (2023) Peach–Potato AphidMyzuspersicae: Current Management Strategies, Challenges, and Proposed Solutions.Sustainability15. , M M A Hafez, M Mahamood, A A Yusuf, P J H King, M F Adil

- 31.Silva V, Alaoui A, Schlünssen V, Vested A, Graumans M et al. (2021) Collection of human and environmental data on pesticide use in Europe and Argentina: Field study protocol for the SPRINT. 16(11), 0259748.

- 32.Z J Ni, Wang X, Shen Y, Thakur K, Han J et al. (2021) Recent updates on the chemistry, bioactivities, mode of action, and industrial applications of plant essential oils.Trends Food Sci. Technol110, 78-89. [Google Scholar] 442 [CrossRef]

- 33.U Ogbonna Confidence, Y Eziah Vincent, O. (2014) . , Bioefficacy of Zingiber officinale againstProstephanustruncatusHorn (Coleoptera: Bostrichidae) infesting 7(2), 177-185.

- 34.Agarwal M, Walia S, Dhingra S, B P Khambay. (2001) Insect growth inhibition, antifeedant and antifungal activity of compounds isolated/derived fromZingiber officinaleRoscoe (ginger) rhizomes.Pest Manag. 57(3), 289-300.

- 35.H M, Awad M, El-Hefny M. (2018) . Insecticidal Activity of Garlic (Allium sativum) and Ginger (Zingiber officinale) Oils on the Cotton Leafworm,Spodoptera littoralis(Boisd.) (Lepidoptera: , M A M Moustafa 26(1), 84-94.

- 36.H S Abdulhay, M.I Yonius (2019)Zingiber officinalean alternative botanical insecticide against black bean aphid (Aphis fabaeScop).Biosci. Available from:www.isisn.org 16(2), 2315-2321.