Abstract

The purpose of this scoping review was to examine the use of Photovoice in caring research. The review assessed the existing literature using the Arksey and O’Malley scoping review methodology. Database searches of relevant literature published worldwide between 1997–2019 yielded 25 articles in the English language that were included in this review. The authors summarized thematic findings. Three themes emerged from data analysis: 1) strengths of using Photovoice; 2) challenges of using Photovoice, and; 3) methodological complexities in Photovoice studies. The small number of studies included in the review (n=25) indicate the limited use of Photovoice in caring research, reflecting missed opportunities for action-oriented research. The scoping review recommends ways that researchers can better address the needs of carers using Photovoice, particularly as a tool for knowledge translation, advocacy, and empowerment.

Author Contributions

Academic Editor: Jong In Kim, Wonkwang University, Korea.

Checked for plagiarism: Yes

Review by: Single-blind

Copyright © 2020 Chloe Ilagan,et.al

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Competing interests

The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

Citation:

Introduction

Background

The reconstruction of the health care system towards community and home care has shifted the responsibilities for care from the public system onto unpaid, informal and familial carers1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6. As health care budgets in many developed nations are increasingly strained, attempts to minimize the costs of institutionalized care have led health care systems to view families as a substitute for formal services, resulting in an increased reliance on families to provide care7,8. As such, the need for carers is expected to increase9. By 2050, the number of seniors aged 60 years or older is expected to double across the globe due to increased life expectancy, as well as healthcare and technological improvements10. Simultaneously, the impacts of trends such as the increase of females in the labour force, a decrease in family sizes, and an aging workforce further strain the demand on carers11, the majority whom are women given the gendered nature of care. In 2012, it was estimated that 28% of the Canadian population were caring for a family member or a friend with a disability or chronic health condition, compared to 12% of the British population, 25–30% of the American population, and 12% of Australians12, 13, 14, 15. Consequently, carers are often touted as the backbone of the health care delivery system16. Benefits of unpaid and familial provision of care include a reduction in health care costs, in terms of health services and institutionalization, while allowing the care recipient to remain at home to maintain a better quality of life 17, 18.

While governments may benefit from reduced costs, the costs for carers who provide care at home increases. Specifically, negative consequences arise from the multiple roles and responsibilities expected of carers5,19,20,21. Oftentimes, carers are not ready for the necessary care tasks and expectations, which can include providing personal care, transportation, house maintenance, financial assistance, emotional support, and scheduling22. Caring has shown negative impacts on mental and physical health, personal finances, time available for other activities, and labour force participation, as many carers balance paid employment in addition to care responsibilities14, 21, 22, 23. As a result, carers have higher levels of stress and depression and lower levels of overall well-being and physical health19, 21, 24, 25.

Photovoice Research Method

Many of the studies examining carers employ quantitative methods. While quantitative studies provide valuable information, such as the number of carers, types of tasks, and the measure or degree of burden, such studies fail to encapsulate the unique and personal experiences of caring9. A growing body of research studies use qualitative methods to address this knowledge gap5,26,27. In recent years, the qualitative research method named Photovoice has seen an increased use in the study of carers9, 28, 29, 30, 31. Understanding what is known about the use of the Photovoice method in existing caring literature is the purpose of this article.

Photovoice is an image-based research method that seeks to examine and understand issues through the everyday experiences of people whose voices are often unheard, forgotten or silenced5,29, 32, 33, 34. As outlined by Wang and Burris (1997), Photovoice has three main goals:

1. To enable people to record and reflect their community’s strengths and concerns;

2. To promote critical dialogue and knowledge about important issues through large and small group discussion of photographs, and;

3. To reach policymakers.

Using a camera, participants record visual evidence of their experiences which allows them to share their unique knowledge and expertise. Photovoice involves participants going out into their community to take pictures that will be used to guide further discussion with the researchers, and in so doing, identifying, representing, and enhancing the visibility of issues within their communities35. Participants function as co-researchers who direct the identification of themes relating to the research question35. As a result, this research method differs from other qualitative methods in that “Photovoice is able to ‘voice’ and represent individual perceptions” of participants,”36(p1). Given participants’ power to voice their experiences is an essential element of empowerment36.

Since its development by Wang and Burris in the mid 1990s, Photovoice has been used in a wide array of research areas to gather information on community strengths and challenges37. Originally used with Chinese village women35, Photovoice research ranges from understanding issues related to mental health38, learning difficulties39, and experiences of cancer survivors40. While the method is used in a wide array of issues and projects, current literature suggests it is underused for caring research. There are numerous benefits of using the method, given the intricacies of care work, which is not only physical, but emotional, social and oftentimes compassionate. Photographs can assist to visually present meanings, ideas and experiences that are not easily communicated through words alone5, 41, 42.

This scoping review will synthesize existing literature to analyze the utility and limitations of Photovoice in examining the caring experience and will likely be of interest to following groups: researchers who have performed Photovoice studies; carers who have participated in these studies, and; policy makers who have the potential to respond to issues found as the result of research. A total of 25 articles written in the English language were included in this review, comprised of peer-reviewed journal articles, government reports and dissertations. All articles examined were published between 1997 and June of 2019.

Methods

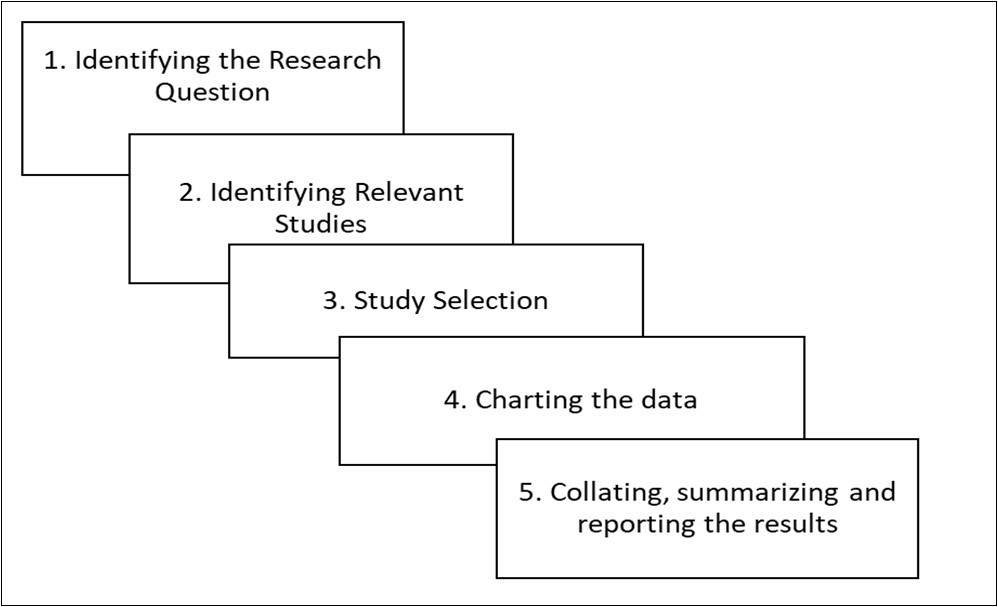

Scoping reviews seek to “map rapidly the key concepts underpinning a research area and the main sources and types of evidence available” 43(p194). Such reviews identify all relevant literature with respect to the volume, nature and characteristics of a research topic and are often used to identify gaps in existing literature44. By examining the depth and the breadth of the existing literature on Photovoice in caring research, this scoping review has the potential to offer a map of our current understanding while informing the use of photovoice method in care-related research. The Arksey and O’Malley framework was chosen to guide the scoping review, as it is an increasingly popular approach for reviews of health research evidence, including carer studies44,45. The framework provides a methodologically rigorous and organized process to address the research question, and consists of 5 stages, as outlined on Figure 1: 1) identifying the research question; 2) identifying relevant studies; 3) study selection; 4) charting the data; and 5) collating, summarizing and reporting the results45.

Figure 1.Arksey and O’Malley (2005) Scoping Review Framework

Stage 1: Identifying the Research Question

The purpose of this study was to determine the current state of Photovoice methods in caring research. The review was guided by the following research question: How does Photovoice methodology contribute to our understanding of carers and caring?

At the onset of the scoping review, the authors defined the scope, parameters and implications of the research question. In some older Photovoice studies, the term “Photovoice” was used interchangeably with terms such as “photo novella” or “photonovel”35. However, “photo novella” and “photonovel” are techniques that have been used to describe the process of using photographs or pictures to tell a story, or to teach language and literacy35. As such, any study that used such terminology was not included in the pool of articles. Further, the authors’ defined carers as people who provide informal and unpaid care for a care recipient above the age of 18 years for health or aging related conditions. This was important to differentiate from other types of carers, such as parents providing care for their children. While wide definitions of search terms can expand the pool of included articles, such searches can also generate a large number of articles. Given the authors’ familiarity with the topic, the search terms were defined from the outset.

Stage 2: Identifying Relevant Studies

A set of articles that was already familiar to the authors was used as a starting point. To ensure an extensive search of all relevant articles, the authors consulted with a university research librarian who provided guidance for the scoping review methodology, forming Boolean search strings, and searching relevant databases. The scoping review included articles published since the inception of Photovoice by Wang and Burris in 1997, through to June 2019. Articles were curated from any geographic location internationally but were limited to those in the English language. An initial and unstructured search was performed using Google Scholar, producing a small but relevant set of articles (n=22). Next, the authors searched databases using search strings as suggested by the university librarian. The following search phrases and keywords were used: informal or unpaid or family or familial or parent or grandparent or spouse or spousal AND carer or carer or caregiv* AND Photovoice or participatory research or photo* method*. The asterisk indicates other possible endings for the root words. Most of the databases had a focus on health and included: Web of Science, Sociological Abstracts, Embase, CINAHL Complete, Factiva, and PyscInfo. Generally, the articles contained a Western bias with many originating from North America. The initial search yielded 418 articles; duplicates were then removed. The remaining abstracts were read and then searched through their reference lists to find other relevant articles. While it is recommended to hand search relevant journals, this was not done due to the large number of journals in health disciplines; it was deemed more productive to go through the reference list of articles that were already identified43. Grey literature was included but yielded few results (n=2). A total of 61 articles were identified.

Stage 3: Study Selection

To filter relevant articles based on the research question, the authors determined inclusion and exclusion criteria. Articles were included in the sample if they addressed each of the following four criteria:1) publication between 1997 and June of 2019; 2) inclusion of Photovoice as a method for data collection; 3) explored the experiences of informal and unpaid carers, and; 4) the carer was caring for a care recipient above the age of 18 years suffering from age or health-related conditions. The authors chose to include studies that also included the following groups in the study sample: care recipients, other family members, and formal health care providers.

Exclusion criteria included: 1) no use of Photovoice as a method of research; 2) care was only provided by formal or paid carers, or did not distinguish between formal and informal carers; 3) the care recipients within the sample included children below 18 years of age. After applying the criteria, 25 articles remained that were then incorporated into the Mendeley database management system. The articles were printed and read in full by the authors.

Stage 4: Charting the Data

During this stage, the authors simultaneously read the articles, applied the inclusion and exclusion criteria, and charted the articles’ themes and concepts. A chart, created using Microsoft Excel, was used to extract and organize the authors’ findings. Charting the data was done through sorting and charting information based on key terms and themes46. The chart consisted of the following fields:

1. Authors and year;

2. Study sample characteristics (a. sample size; b. relationship to care receiver; c. condition/disease/other inclusion criteria of care recipient);

3. Methods (a. details of research process; b. other qualitative/quantitative methods used with Photovoice);

4. Findings and results, and;

5. Conclusions (implications for carers, researchers, policy makers).

After analyzing articles for relevance and content, the authors determined if the article matched the inclusion criteria. If the authors were unsure, they discussed and jointly decided the article concerned should be included.

Stage 5: Collating, Summarizing, and Reporting the Results

Of the 25 articles that were included, 20 (80%) were peer-reviewed primary research articles. Three articles (12%) were dissertations and two articles (8%) were academic/government reports. The geographical distribution of studies included Canada (n=8), the United States (n=8), Australia (n=4), United Kingdom (n=3), Netherlands (n=1), New Zealand (n=1), and Portugal (n=1). The authors collaborated to compare and discuss common findings amongst the articles. The results of the thematic analysis are described in the following section.

Findings

The authors identified the following themes: 1) strengths of using Photovoice in research on caring; 2) challenges of using Photovoice in research on caring; and 3) methodological complexities.

Theme 1: Strengths of Using Photovoice in Research on Caring

The scoping review revealed four strengths of the Photovoice method in caring research: (a) a positive experience for carers; (b) facilitating communication of novel and abstract ideas, (c) participant cohesion, and (d) collaboration in research. Each of these strengths is discussed below as subthemes.

Positive Experience for Participants

Previous studies have found that the Photovoice process allows researchers to engage fully with participants because of the presence and stimulus of visual cues (Hibberd, Keady, Reed & Lemmer, 2009; Young & Barrett, 2001). A few of the studies noted that carers found the research process enjoyable34,47, engaging34, and in some cases, therapeutic48. In Armstrong (2012), participants stated that the organization, choice, and discussion of photographs in the focus group was very helpful and therapeutic, as they were able to make sense of their experiences and relate to those in similar circumstances. Sethi (2014) noted that participants were excited and honoured to have their pictures displayed in an art exhibit as part of the knowledge translation phase of the project. Many of the participants felt empowered and emotional from the recognition that their photographs could be used to bring awareness and educate others34.

Facilitating Communication of Novel and Abstract Ideas

Photovoice can allow for the ease of communication between researchers and participants. The Photovoice methodology is useful when collecting data from participants that have low literacy or are not fluent in the language of the researchers47,49. The facilitation of communication using Photovoice is also important when discussing abstract issues that may be hard to articulate, such as the emotionally distressing aspects of caring. This was noted by Wong et al. (2018), in which Photovoice was chosen due to the merits of its participatory approach in studying distressed and understudied groups.

Photovoice allows participants to be in control of the research process; this is especially important when discussing topics that may be difficult to explore. For instance, Horsfall, Leonard, Evans & Armitage (2010) identified and analyzed the social networks of older people and their carers, choosing Photovoice because social networks are often “invisible, not talked about, or are seen as an unremarkable part of people’s everyday lives”15(p9). Photovoice has proven to be an effective methodological process in gerontological research50. Participant control of the research process is particularly critical when researchers delve into emotional and sensitive topics that could leave participants feeling vulnerable51.

Researchers in three studies noted that Photovoice enabled the emergence of overlooked, ignored, or under conceptualized aspects of the caring role9,28,41. For example, Garner & Faucher (2014) used Photovoice to examine the challenges experienced and the supports employed by family carers. They identified the following novel challenges faced by carers: the management of equipment and various treatments, and problem-solving using trial and error9. Aubeeluck & Buchanan (2006) explored familial carers of Huntington Disease patients and noted that the themes of care, security and small pleasures were not readily identifiable in previous Huntington Disease caring literature.

Participant Cohesion

Many of the articles analyzed (n=18) recruited samples of carers who were caring for recipients that were suffering from a common disease or condition. For instance, Guerra, Rodrigues, Demain, Figueiredo & Sousa (2012) studied family carers of dementia patients. Common characteristics amongst the study sample allowed for a greater sense of community and cohesion due to shared experiences, common needs, and challenges. In LaDonna (2014), some participants had not met other individuals outside of their families who had Myotonic Dystrophy Type 1. Participation in the research study allowed participants to meet, socialize and bond with other affected individuals, which may have contributed to participants’ assessment of the research process as “therapeutic”47. A participant in Levy et al.’s (2019) study echoed this sentiment by describing the Photovoice experience as “healing”52(p561). Similarly, in a study by Williamson et al. (2019), researchers noted that common lived experiences between participants allowed for the emergence of strong relationships. The researchers also noted that some of these relationships continued after the study, as participants and community members continued to collaborate in capacity building and awareness efforts53.

Collaboration in Research

Research suggests that carers are given little help from health care professionals when performing tasks and when dealing with the emotional demands of caring54. However, caring does not need to be an isolating experience. While existing literature highlights negative aspects experienced by carers, strong social networks and collaboration amongst all groups concerned may better support carers; these groups include the care recipient (s), other family members, paid health care providers, and, volunteers15. Exposure to different perspectives during the research process can assist in better understanding the overall caring experience. In turn, this can help inform health care providers and other stakeholders who have a vested interest in supporting the needs of carers and care recipients. Thus, the needs of carers must be understood within the wider context of formal services, workplace supports, interventions, and policies55. Much of the time family carers are unsure of when they need the available resources, or how to access and use these crucial services and supports56,57, which exemplifies the importance of developing and maintaining connections with other concerned groups, making caring more sustainable15.

Theme 2: Challenges of Using Photovoice in Research on Caring

This section addresses the challenges identified in the articles included in the review, including: (a) time and cost demands, (b) memory bias, and (c) photograph selection bias.

Time and Cost Demands

Photovoice projects can be costly; all the 25 articles chosen by the authors either provided or lent participants a camera. Additional costs include: using a digital camera as opposed to a disposable camera; film, and processing fees. In additional to financial costs, Photovoice research are very time consuming, which can be problematic given the time constraints already experienced by carers34,35. Time and energy are invested by participants through partaking in multiple meetings with the researcher, taking photographs, and follow-up interviews or focus groups34,53,58. In Williamson et al. (2019), some participants required more support in using their cameras and maintaining communication with the project. These demands can cause participants to refuse to participate or leave the study. One exception to this finding was Aubeeluck & Buchanan’s (2006) study, which noted that Photovoice required only a small time commitment from participants. However, multiple meetings and interviews/focus groups may be necessary for researchers to build rapport and trust with the participants. In turn, this would allow participants to uncover deeper meanings in their photographs and experiences through greater reflection59. To address time and energy demands, as well as the issue of attrition, researchers often provide compensation for participants to take part and complete the study. Compensation options include cash, gift cards, transportation money, or the digital camera that was used in the study8,9,60.

Memory Bias

Another challenge lies in the fact that Photovoice is a retrospective method, which leads to possible memory bias. During the interview or focus group phase, participants are asked to recall how they felt and what their experiences were like when they first took their photographs, opening up the possibility of recall bias28. Some studies had significant time periods between the time when participants took pictures and met for discussion; these time periods may be as long as eight months61. While memory issues cannot be eliminated completely, researchers made efforts to mitigate these effects. For example, researchers provided participants with a notebook or diary to record details during the research process, or asked participants to craft accompanying narratives during the picture taking process34,61.

Photograph Selection Bias

Some of the carers’ experiences may contribute to them being identified as more memorable, and thus more photographed (Guerra, Rodrigues, Demain, Figueiredo, & Sousa, 2013). Participants may choose photographs that highlight positive aspects of caring worth memorializing in photographs. Guerra et al. (2012) also suggested that participants may have a cultural bias towards the photographs they choose to take. As with other qualitative and quantitative research methods, researchers must be mindful of participants providing responses that they believe the researchers are looking for62.

It should be noted that the challenges outlined above are not limited to research with carers; such challenges have been seen in Photovoice with other participant groups and in other fields of research.

Theme 3: Methodological Complexities

The following section explores the methodological complexities of using Photovoice, as identified from the 25 articles. The following subthemes emerged: (a) methodological challenges, (b) alternate research approaches, and (c) ethical considerations.

Methodological Challenges

Certain controlled, research-directed settings can create an authoritarian environment which may shift away from a participant-directed research process39,58. In such research, participants may perceive research questions being asked by the researchers as too complex. In van Hoof et al.’s (2016) Photovoice study on the sense of home in nursing homes, participants provided feedback that the abstract phenomenon of “sense of home” was difficult to comprehend and thus capture in a photograph. Complexity of the research process may affect study findings in other ways. In van Hoof et al., (2016), participants were told that the camera reel had 25 pictures but were free to choose the number of pictures they could take. Some participants gave feedback that taking 25 pictures was too much and thus decided to take random photographs in the end to fill up the camera reel63. These challenges may be alleviated through open communication, discussion, and guidance from the researchers to ensure that participants fully understand the intricacies of the study.

Alternate Research Approaches

Many of the studies in this review used modified aspects of the traditional Photovoice method, originated by Wang and Burris (1994). Although there are no set guidelines in undertaking a Photovoice study, the following steps are generally represented: an orientation meeting, focus groups and/or individual interviews, and a group forum to share findings. The rationale for altering the Photovoice method varied from researcher to researcher. For example, some studies opted to use individual interviews as opposed to focus groups to discuss participant photographs. In Sethi (2014) and Roger, Migliardi, & Mignone (2012), the researchers were concerned with the use of large focus groups as participants may not be comfortable discussing intimate issues in such a format. Other modifications include not involving participants in the data analysis stage even though Photovoice, as stated earlier, is based on the tenets of participatory research.

Our analysis found that some studies used other qualitative methods in conjunction with Photovoice during the data collection phase. The use of other methods in conjunction with Photovoice may offer a richer understanding of participants’ experiences. A scoping review of Photovoice literature in 2012 found that out of 191 studies, 55% used Photovoice as the sole method for data collection and analysis, while the remaining 45% used Photovoice in addition to other methodological approaches64. Our scoping study found that 40% (n=10) of studies used Photovoice as the only research method, while 52% (n=13) of studies used Photovoice in conjunction with another type of qualitative method. Other qualitative methods used include content analysis, and individual interviews (as opposed to group discussion)60. One study employed Photovoice together with quantitative methods.

Ethical Considerations

It is of utmost importance for researchers ensure the participants’ confidentiality and anonymity. Ethical issues during the use of Photovoice include the following: invasion of privacy; issues in recruitment; participation; representation, and; advocacy. Methods taken by the researchers to ensure confidentiality included: obtaining ethical approval from research boards; discussing ethical issues that may arise during the photography process; signing consent forms; allowing participants to withdraw at any time point, and; providing pseudonyms. In one of the few studies to directly state ethics concerns that had arisen during the Photovoice studies, Sethi (2014) noted that researchers must be cautious of this innovative methodology; Photovoice may not be suitable for participants whose safety has been a concern due to political issues in their country, for example. In Sethi’s (2014) study, three participants who were refugees shared their stories but did not take photographs. While no studies explicitly mentioned that potential participants decided to not partake or to withdraw from the study due to ethical concerns, researchers must continue to be cognizant, sensitive, and accommodating of these issues.

Discussion

Some studies in this review fell short in disseminating research findings through knowledge mobilization and knowledge translation strategies. In particular, only 60% (n=15) of articles included some photographs from the data collection phase in the journal article8, 15, 31, 34, 41, 47, 48, 61, 62, 65, 66, 67, 68, 69. Inclusion of the photos, alongside the narratives of participants within the published research papers, can operate as a form of disseminating research findings in the research community. However, it is entirely possible that the exclusion of photographs was set by pre-determined requirements of the academic journals concerned70. As researchers continue to diversify methods, journals need to explore the inclusion of photographs.

As outlined by Wang and Burris, one of the goals of Photovoice is to reach policymakers71. There lies an inherent assumption that Photovoice can enable change in the community through decision-making and policies. Photovoice studies can be an effective advocacy tool to inform stakeholders of the caring experience. In Levy et al. (2019), participants noted “the opportunity to teach the community as important”52(p561). However, few studies intentionally addressed that goal. Of the 25 articles reviewed, three studies included art exhibits, where community stakeholders such as health providers, carer organizations, higher education institutions, and policy makers were invited to attend9, 52, 72. Four studies stated that art exhibits will be planned/are in the planning process15, 29, 34, 73. An important component of using Photovoice is “what is done after the pictures have been taken and the discussion has occurred”72(p632). Photographs can facilitate discussion and dialogue amongst others who view the pictures72. The presentation of photographs to a wider audience can help educate and inform others, such as policy makers who have the potential to make change and provide support for carers. The absence of next steps from a number of the articles limits the potential for such research to reach the community at large. The gap between research findings and opportunities for community change may also be narrowed through collaboration between participants and researchers, ideally at the beginning of the research process, to discuss tailored services, programs, and policy changes that support carer needs68. Other studies have noted that this requires relationship building prior to and during the Photovoice process as well as the political desire to bring about change in the community74.

Although one of the goals of Photovoice is to empower participants, information on evaluating and achieving this goal may be lacking. Few studies mention or allude to ways in which partaking in Photovoice research studies can be advantageous and beneficial for participants. In Sethi (2014), participants had a sense of pride and ownership in the photographs they had taken, such that some were excited to show the researcher their photographs. Given that participants in that study may feel a sense of empowerment after completing the project, future research studies can further explore how Photovoice may be used as an empowerment tool for carers. Some studies mention that carers are better able to make sense of their caring situation41, 48, 52. Aubeeluck & Buchanan (2006) and Levy et. al (2019) noted that carers were able to record and reflect the positive aspects of their lives and the problems that they experienced after participation in the project. However, there is a lack of research on whether involvement in Photovoice projects can lead to tangible or measurable changes in the lives of carers, such as improved problem solving and dealing with challenges while caring.

There are a wide range of new research directions in the area of caring that have yet to be tapped when using Photovoice methodology; three will be discussed here. First, immigrants are providing transnational care across international borders in increasing numbers given current trends in globalization and technological advances. Sethi (2014) found that study participants rely on their families abroad for social support through computer and phone message applications, phone and video calls. More research can be done to explore transnational caring and the ties that immigrants have to care recipients in other countries. Photovoice can be used to understand such unique experiences, which can be useful in policy making to help support these carers. Second, exploring the negotiations that double-duty carers have to make when transitioning between their paid caring work, whether in an institutional setting or in the community, and their unpaid/ informal care work, whether in an institutional setting, in the community, or at home. Third, intersectionality theory can be integrated in Photovoice research on carers. Intersectionality theory suggests that the interactions between various social categories, such as race, class, and gender shapes an individual’s personal experiences34,75. Other Photovoice studies have acknowledged that such contextual factors play a significant role in participants’ lived realities, using Photovoice to allow participants to portray their lives through their own eyes and in their own way75. The lens of intersectionality can be used in future research studies to explore how carers’ experiences are affected by these overlapping axes of diversity.

Limitations

There are numerous limitations of this scoping review. Limitations include the lack of inclusion of the literature outside of the English language and regions outside of the Western sphere of influence. Further, all included papers would have been more thoroughly reviewed if all four authors read and discussed each one, thus providing a cross-check. The final limitation is the possibility of missed articles when using the database searching techniques employed.

Conclusions

Employing the scoping review framework offered by Arksey and O’Malley (2005), this paper has synthesized caring research which has employed Photovoice. Through reviewing in detail the 25 articles that met the inclusion criteria, the authors identified the following key themes: strengths and challenges of using Photovoice; methodological complexities; research gaps, and new research directions. Most of the articles analyzed for this review were primary research articles from peer-reviewed journals. The authors found that photographs taken during the research provided a unique lens into the intimate experiences and everyday realities of these carers by bringing to light the rewards and conflicts experienced. In particular, the articles in totality illustrated that carers are critical players who support the health of their recipients. The limited use of Photovoice in caring research may reflect missed opportunities for action-oriented research, which may greatly impact the lives and experiences of carers64. Overall, Photovoice can effectively be used as an advocacy and empowerment tool for caring research to foster social change in vulnerable groups and communities.

Affiliations

CI, ZA, AW: School of Earth, Environment, and Society, McMaster University; BS: School of Social Work, King’s University College, University of Western Ontario

Acknowledgements

This research was funded by a Canadian Institutes of Health Research‐Institute for Gender and Health, Research Chair in Gender, Work & Health, addressing Caregiver‐Friendly Workplace Policies (MOP-60484).

References

- 1.Armstrong P, Cornish M. (1997) Restructuring Pay Equity for A Restructured Work Force: Canadian Perspectives. , Gender, Work & Organization 4(2), 67-86.

- 2.Coyte P C, McKeever P. (2016) Home Care in Canada: Passing the Buck. , Canadian Journal of Nursing Research Archive 33(2).

- 3.Fast J E, Williamson D L, Keating N C. (2001) The hidden costs of informal elder care. , Family Economics and Nutrition Review 120, 1-13.

- 4.Lilly M L. University of Toronto (2008) The Labour Supply of Unpaid Caregivers in Canada [Doctoral Thesis]. http://hdl.handle.net/1807/11226

- 5.Sethi B, Williams A, Desjardins E, Zhu H, Shen E. (2017) Family conflict and future concerns: Opportunities for social workers to better support Chinese immigrant caregiver employees. , Journal of Gerontological Social Work 61(4), 375-392.

- 6.Stabile M, Laporte A, Coyte P C. (2006) Household responses to public home care programs. , Journal of Health Economics 25(4), 674-701.

- 7.Funk L M. (2013) Home Healthcare and Family Responsibility: A Critical Discourse Analysis of Talk and Text. Healthcare Policy.(accessed2020,Jun 30).9:. 86-97.

- 8.Mignone J, Migliardi P, Harvey C, Davis J, Madariaga-Vignudo L. (2015) HIV as Chronic Illness: Caregiving and Social Networks in a Vulnerable Population. , Journal of the Association of Nurses in AIDS Care 26(3), 235-245.

- 9.Garner S L, Faucher M A. (2014) Perceived Challenges and Supports Experienced by the Family Caregiver of the Older Adult: A Photovoice Study. , Journal of Community Health Nursing 31(2), 63-74.

- 11. (2015) Employer Panel for Caregivers. When work and caregiving collide: how employers can support their employees who are caregivers. Ottawa: Employment and Social Development Canada, Government of Canada.

- 12.Anderson L A, Edwards V J, Pearson W S, Talley R C, McGuire L C. (2013) Adult Caregivers in the United States: Characteristics and Differences in Well-being, by Caregiver Age and Caregiving Status. Preventing Chronic Disease. 10, 1-6.

- 14.Fast J, Lero D, DeMarco R, Ferreira H, Eales J. (2014) care work and paid work: Is it sustainable? Edmonton:University of Alberta, Research on Aging, Policies, and Practices (RAPP).

- 15.Horsfall D, Leonard R, Evans S P, Armitage L. (2010) Care Networks Project: Growing and Maintaining Social Networks for Older People. , Perth, NSW: Western Sydney Univesrity

- 16.Stajduhar K I, Funk L, Toye C, Grande G E, Aoun S. (2001) Part 1: Home-based family caregiving at the end of life: a comprehensive review of published quantitative research (1998-2008). Palliative Medicine. 24(6), 573-593.

- 17.Turcotte M. (2013) caregiving: What are the consequences?. Insights on Canadian Society.http://www.statcan.gc.ca/pub/75-006-x/2013001/article/11858-eng.pdf 16.

- 18.Van Houtven CH, Norton E C.(20014) Informal care and health care use of older adults. , Journal of Health Economics 23(6), 1159-1180.

- 19.Bauer J M, Sousa-Poza A. (2015) Impacts of Informal Caregiving on Caregiver Employment, Health, and Family. , Journal of Population Ageing 113, 3-8.

- 20.Clemmer S J, Ward-Griffin C, Forbes D. (2008) Family Members Providing Home-Based Palliative Care to Older Adults: The Enactment of Multiple Roles. Canadian Journal on Aging / La Revue canadienne du vieillissement. 27(3), 267-283.

- 21.Pinquart M, Sörensen S. (2003) Differences between caregivers and noncaregivers in psychological health and physical health: A meta-analysis. , Psychology and Aging 18(2), 250-267.

- 22.Sinha M. (2015) Portrait of caregivers,2012.Statistics Canada.https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/pub/89-652-x/89-652-x2013001-eng.htm.

- 23.Dembe A E, Partridge J S. (2011) The Benefits of Employer-Sponsored Elder Care Programs: Case Studies and Policy Recommendations. , Journal of Workplace Behavioral Health 26(3), 252-270.

- 24.Pinquart M, Sörensen S. (2007) Correlates of Physical Health of Informal Caregivers: A Meta-Analysis. , The Journals of Gerontology: Series B 62(2), 126-137.

- 25.Schulz R, Sherwood P R. (2008) Physical and mental health effects of family caring. , Journal of Social Work Education 44(3), 105-113.

- 26.Lane P, McKenna H, Ryan A, Fleming P. (2003) The Experience of the Family Caregivers’ Role: A Qualitative Study. Research and Theory for Nursing Practice. 17(2), 137-151.

- 27.Tseng C-N, Huang G-S, Yu P-J, Lou M-F.. (2015).A Qualitative Study of Family Caregiver Experiences of Managing Incontinence in Stroke Survivors. PLOS ONE 10(6), 1-13.

- 28.Angelo J, Egan R. (2015) Family caregivers voice their needs: A photovoice study. , Palliative & Supportive Care 13(3), 701-712.

- 29.Faucher M A, Garner S L. (2015) A method comparison of photovoice and content analysis: research examining challenges and supports of family caregivers. , Applied Nursing Research 28(4), 262-267.

- 31.Williams K L, Morrison V, Robinson C A. (2014) Exploring caregiving experiences: caregiver coping and making sense of illness. , Aging & Mental Health 18(5), 600-609.

- 32.Catalani C, Minkler M. (2010) Photovoice: A Review of the Literature. in Health and Public Health. Health Education & Behavior 37(3), 424-451.

- 33.Foster-Fishman P, Nowell B, Deacon Z, Nievar M A, McCann P. (2005) Using Methods That Matter: The Impact of Reflection, Dialogue, and Voice. , American Journal of Community Psychology.36(3–4): 275-291.

- 34.Sethi B. (2014) Intersectional Exposures: Exploring the Health Effect of Employment with KAAJAL Immigrant/Refugee Women in Grand Erie through Photovoice. Wilfrid Laurier University. https://scholars.wlu.ca/etd/1659

- 35.Wang C, Burris M A. (1997) Photovoice: Concept, Methodology, and Use for Participatory Needs Assessment. , Health Education & Behavior 369, 3-24.

- 36.Budig K, Diez J, Conde P, Sastre M, Hernán M. (2018) Photovoice and empowerment: evaluating the transformative potential of a participatory action research project. , BMC Public Health 432, 1-18.

- 37.Wang C C. (1999) Photovoice: A Participatory Action Research Strategy Applied to Women’s Health. , Journal of Women’s Health 8(2), 185-192.

- 38.N De Vecchi, Kenny A, Dickson‐Swift V, Kidd S. (2016) How digital storytelling is used in mental health: A scoping review. , International Journal of Mental Health Nursing 25(3), 183-193.

- 39.Booth T, Booth W. (2003) In the Frame: Photovoice and mothers with learning difficulties. , Disability & Society 18(4), 431-442.

- 40.Kim M A, Yi J, Sang J, Kim S H, Heo I. (2016) Experiences of Korean mothers of children with cancer: A Photovoice study. , Journal of Psychosocial Oncology 35(2), 128-147.

- 41.Aubeeluck A, Buchanan H. (2006) Capturing the Huntington’s disease spousal carer experience: A preliminary investigation using the ‘Photovoice’ method. , Dementia 5(1), 95-116.

- 42.Young L, Barrett H. (2001) Ethics and Participation: Reflections on Research with Street Children. , Ethics, Place & Environment 4(2), 130-134.

- 43.Mays N, Roberts E, Popay J. (2001) Synthesising research evidence. In: Studying the Organisation and Delivery of Health Services: Research Methods. , London: Routledge 188-220.

- 44.Arksey H, O’Malley L. (2005) Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework. , International Journal of Social Research Methodology 8(1), 19-32.

- 45.Davis K, Drey N, Gould D. (2009) What are scoping studies? A review of the nursing literature. , International Journal of Nursing Studies 46(10), 1386-1400.

- 46.Ritchie J, Spencer L. (1994) Qualitative data analysis for applied policy research. Analysing Qualitative Data In: Bryman A, Burgess RG, editors , London: 173-194.

- 47.LaDonna K A. University of Western (2014) Are Patients at the Centre of Care?: A Qualitative Exploration of Myotonic Dystrophy Type 1 (DM1) [Doctoral Thesis]. , Ontario. https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/etd/2634

- 48.Armstrong M L. University of Florida (2012) Using Photovoice to Assess Quality of Life in Individuals Impacted by Advanced Gynecologic Malignancies.

- 49.JPK Ninnoni. (2011) Effective communication with people with learning disabilities with epilepsy and their carers. [PhD Thesis]. Robert Gordon Thesis. https://rgu-repository.worktribe.com/output/248116/effective-communication-with-people-with-learning-disabilities-with-epilepsy-and-their-carers

- 50.Mysyuk Y, Huisman M. (2019) Photovoice method with older persons: a review. , Ageing & Society 40(8), 1759-1787.

- 51.Horsfall D, Noonan K, Leonard R. (2012) Bringing our dying home: How caring for someone at end of life builds social capital and develops compassionate communities. , Health Sociology Review 21(4), 373-382.

- 52.Levy K, Grant P C, Depner R M, Tenzek K E, Pailler M E. (2019) The Photographs of Meaning Program for Pediatric Palliative Caregivers: Feasibility of a Novel Meaning-Making Intervention. , American Journal of Hospice and Palliative Medicine 36(7), 557-563.

- 53.Williamson H J, Brennan A C, Tress S F, Joseph D H, Baldwin J A. (2019) Exploring health and wellness among Native American adults with intellectual and/or developmental disabilities and their family caregivers. , Journal of Applied Research in Intellectual Disabilities 33(3), 327-333.

- 54.Reinhard S C, Given B, Petlick N H, Bemis A. (2008) Chapter 14: Supporting Family Caregivers. Patient Safety and Quality: An Evidence-Based Handbook for Nurses. Rockville (MD): Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (US). (Advances in Patient Safety). http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK2665/ in Providing Care. In: Hughes RG, editor .

- 55.Funk L M, Stajduhar K I. (2009) Interviewing Family Caregivers: Implications of the Caregiving Context for the Research Interview. , Qualitative Health Research 19(6), 859-867.

- 56.Given B A, Given C W, Stommel M, Lin C-S. (1994) Predictors of Use of Secondary Carers Used by the Elderly Following Hospital Discharge. , Journal of Aging and Health 6(3), 353-376.

- 57.Maynard K, Ilagan C, Sethi B, Williams A. (2018) Gender-based analysis of working-carer men: a North American scoping review. , International Journal of Care and Caring 2(1), 27-48.

- 58.Sutton-Brown C A. (2014) Photovoice: A Methodological Guide. , Photography and Culture 7(2), 169-185.

- 59.Kantrowitz-Gordon I, Vandermause R. (2016) Metaphors of Distress: Photo-Elicitation Enhances a Discourse Analysis of Parents’ Accounts. , Qualitative Health Research 226(8), 1031-1043.

- 60.Roger K, Migliardi P, Mignone J. (2012) HIV, Social Support, and Care Among Vulnerable Women. , Journal of Community Psychology 40(5), 487-500.

- 61.Hibberd P, Keady J, Reed J, Lemmer B. (2009) Using photographs and narratives to contextualise and map the experience of caring for a person with dementia. , Journal of Nursing and Healthcare of Chronic Illness 1(3), 215-228.

- 62.Lang A, Macdonald M, Marck P, Toon L, Griffin M. (2015) Seniors managing multiple medications: using mixed methods to view the home care safety lens. , BMC Health Services Research 548, 1-15.

- 63.J Van Hoof, Verbeek H, Janssen B M, Eijkelenboom A, Molony S L et al. (2016) A three perspective study of the sense of home of nursing home residents: the views of residents, care professionals and relatives. , BMC Geriatrics 169, 1-16.

- 64.Lal S, Jarus T, Suto M J. (2012) A Scoping Review of the Photovoice Method: Implications for Occupational Therapy Research. , Canadian Journal of Occupational Therapy 79(3), 181-190.

- 65.Argyle E, Downs M, Tasker J. University of Nottingham (2010) Continuing to care for people with dementia: Irish family carers’ experience of their relative’s transition to a nursing home. http://hdl.handle.net/10147/141260

- 66.Guerra S R, Rodrigues S P, Demain S, Figueiredo D M, Sousa L X. (2012) Evaluating proFamilies-dementia: Adopting photovoice to capture clinical significance. , Dementia 12(5), 569-587.

- 67.Hammond C, Thomas R, Gifford W, Poudrier J, Hamilton R et al. (2017) Cycles of silence: First Nations women overcoming social and historical barriers in supportive cancer care. , Psycho-Oncology 26(2), 191-198.

- 68.EDS López, Eng E, Randall-David E, Robinson N. (2005) Quality-of-Life Concerns of African American Breast Cancer Survivors Within Rural North Carolina: Blending the Techniques of Photovoice and Grounded Theory: Qualitative Health Research. 15(1), 99-115.

- 69.Wong S S, George T J, Godfrey M, J Pereira DB Le. (2018) Using photography to explore psychological distress in patients with pancreatic cancer and their caregivers: a qualitative study. Supportive Care in Cancer. 27(1), 321-328.

- 71.Wang C, Burris M A. (1994) Empowerment through Photo Novella: Portraits of Participation. Health Education Quarterly. 21(2), 171-186.

- 72.Mosavel M, Sanders K D. (2010) Photovoice: A Needs Assessment of African American Cancer Survivors. , Journal of Psychosocial Oncology 28(6), 630-643.

- 73.Pace J E. (2016) O2-12-05: Focusing on Dementia: Using Photovoice to Document Southern Labrador Inuit Experiences of Cognitive Decline. Alzheimer’s & Dementia. 12(7), 259.

Cited by (9)

- 1.Sethi Bharati, Williams Allison, Leung Joyce L. S., 2022, Caregiving Across International Borders: a Systematic Review of Literature on Transnational Carer-Employees, Journal of Cross-Cultural Gerontology, 37(4), 427, 10.1007/s10823-022-09468-w

- 2.Duijs Saskia Elise, Abma Tineke, Schrijver Janine, Bourik Zohra, Abena-Jaspers Yvonne, et al, 2022, Navigating Voice, Vocabulary and Silence: Developing Critical Consciousness in a Photovoice Project with (Un)Paid Care Workers in Long-Term Care, International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(9), 5570, 10.3390/ijerph19095570

- 3.Sanjigadu Sebastian, 2024, The Road Less Travelled: Exploring the Planning and Preparation for a Critical Social Justice Module by the University of Kwa-Zulu Natal, South Africa, E-Journal of Humanities, Arts and Social Sciences, (), 61, 10.38159/ehass.20245125

- 4.Bowness Bryher, Henderson Claire, Akhter Khan Samia C., Akiba Mia, Lawrence Vanessa, 2024, Participatory research with carers: A systematic review and narrative synthesis, Health Expectations, 27(1), 10.1111/hex.13940

- 5.Karuga Robinson, Steege Rosie, Njoroge Inviolata, Liani Millicent, Wiltgen Georgi Neele, et al, 2022, Leaving No One Behind: A Photovoice Case Study on Vulnerability and Wellbeing of Children Heading Households in Two Informal Settlements in Nairobi, Social Sciences, 11(7), 296, 10.3390/socsci11070296

- 6.Jenkins Emerald, Szanton Sarah, Hornstein Erika, Reiff Jenni Seale, Seau Quinn, et al, 2025, The use of photovoice to explore the physical disability experience in older adults with mild cognitive impairment/early dementia, Dementia, 24(1), 40, 10.1177/14713012241272754

- 7.Karuga Robinson, Kabaria Caroline, Chumo Ivy, Okoth Linet, Njoroge Inviolata, et al, 2023, Voices and challenges of marginalized and vulnerable groups in urban informal settlements in Nairobi, Kenya: building on a spectrum of community-based participatory research approaches, Frontiers in Public Health, 11(), 10.3389/fpubh.2023.1175326

- 8.Tenzek Kelly E., Lattimer Tahleen A., Levy Kathryn, Grant Pei C., Depner Rachel M., et al, 2024, Pushing the boundaries: an evaluation of the Photographs of Meaning (POM) program for pediatric palliative caregivers (PPCGs), Journal of Applied Communication Research, 52(4), 534, 10.1080/00909882.2024.2376039

- 9.Darling Wesley, Broader Jacquelyn, Cohen Adam, Shaheen Susan, 2023, Going My Way? Understanding Curb Management and Incentive Policies to Increase Pooling Service Use and Public Transit Linkages in the San Francisco Bay Area, Sustainability, 15(18), 13964, 10.3390/su151813964