Factors Impacting Nutritional Status in Infants with Single Ventricle Physiology

Abstract

Infants with single ventricle (SV) physiology are at increased risk of undernutrition, which can contribute to adverse outcomes. This is a retrospective case series examining factors associated with undernutrition in patients with SV physiology at one year of age. It includes 56 infants from a single institution who underwent SV palliation between 2003 and 2023. Undernutrition was defined as a weight-for-length z-score (WLZ) below -1, based on World Health Organization (WHO) normative data. Independent variables included surgical interventions, cardiorespiratory factors, and nutritional interventions. Associations between these variables and nutritional status were assessed using Fisher’s exact test. At one year, a total of nine infants (16%) were undernourished. Undernutrition rates significantly declined after 2013 (p=0.02), demonstrating improvements in nutritional outcomes over our study period. Those who used supplemental oxygen or pulmonary medications were undernourished at lower rates. While this difference was not statistically significant, the number of undernourished patients in the cohort may have limited the study’s power. Our findings suggest that early respiratory interventions may provide nutritional benefits in infants with SV physiology.

Author Contributions

Copyright © 2025 Mark Gormley, et al.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Competing interests

There are no relevant conflicts of interest amongst the study authors.

Citation:

Introduction

Single ventricle (SV) physiology refers to a form of severe congenital heart disease (CHD) characterized by the presence of only one functional or anatomic ventricle1, which accounts for nearly 10% of all congenital heart defects2. This heterogeneous condition arises from various embryological malformations.

Children with a SV typically undergo a series of palliative surgeries to optimize systemic and pulmonary blood flow, often including a Norwood procedure and bidirectional Glenn (BDG) procedure followed by a Fontan procedure3. Despite advances in care for SV patients, these patients continue to face significant challenges, including difficulty achieving adequate nutritional status3, 4, 5, 6, 7.

Nutritional status can be quantified using weight-for-length z-score (WLZ) which is a measure of a patient’s weight and length compared to the average child’s of the same age. Undernutrition, specifically wasting, can be defined as WLZ below -1 or dropping major age-indexed z-scores4, 8, 9, 10.

Nutritional outcomes in SV physiology are thought to be impacted by factors such as surgical interventions, prolonged hospital courses, lengthy sedations, surgical complications, abnormal hemodynamics, hypoxemia, frequent respiratory infections, hypermetabolic needs, and oral-motor feeding difficulties3, 5, 6, 11.

Undernourished patients have poorer surgical recovery, neurodevelopmental outcomes12, 13, 14, 15, and heightened risk of social, emotional, and attention impairments16. Micronutrient deficiencies in undernourished patients contribute to immune dysfunction, increasing rates of postoperative infections and delayed wound healing17. Malnourished infants with a single ventricle also face longer hospitalizations compared to well-nourished peers, independent of hemodynamic or echocardiographic indices18.

Despite wide recognition of undernutrition among this population, there is limited research examining the factors that impact these patients’ growth. Most existing literature focuses on nutritional status at the time of the Glenn procedure4, 5, 19 or earlier6, leaving a gap in understanding how longer-term variables, such as surgical timing and other perioperative factors, impact growth outcomes.

This study was designed to identify factors associated with undernutrition at 12 months of age in infants with SV physiology. By analyzing an extended period of nutritional and clinical data, this research aims to clarify the variables that predict poor nutritional outcomes and provide insights to guide earlier interventions for those at greatest risk of undernutrition. Understanding the way in which these factors affect nutritional outcomes is critical to improve long-term outcomes for this vulnerable population.

Materials and Methods

Participants

This was a retrospective case series of all patients with SV physiology treated at the University of Minnesota Medical Center between 2003 and 2023. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Boards (IRB) at the University of Minnesota and at Eastern Virginia Medical School. Patients were identified using the UMN Single Ventricle (SV) database. A waiver of individual patient consent was approved, and patients who declined to participate in research were excluded. Exclusion criteria included unavailable nutritional data between nine months and 15 months, chromosomal anomalies, and those deceased before one year of age.

Measurements

Anthropometric measurements, including weight-for-age (WAZ), length-for-age (LAZ), and weight-for-length z-scores (WLZ), were recorded closest to one year of age using World Health Organization (WHO) growth charts. Undernutrition categories reflected WHO child growth standards, with WLZ of -1 to -2 designating mild undernutrition, -2 to -3 designating moderate undernutrition, and less than -3 designating severe undernutrition8, 9. A decrease of two major age-indexed z-scores was classified as moderate undernutrition and a decrease of three z-scores was classified as severe undernutrition8, 9. The primary outcome measure was undernutrition.

Variables investigated included surgical interventions, surgical complications, hospital course, cardiorespiratory factors, and nutritional interventions. Demographic information, including gender and self-identified race, was also collected.

Data Analysis

Participant demographic and clinical characteristics were summarized using mean (SD) for continuous variables and count (%) for categorical variables, overall and by nutrition status. Fisher’s exact tests for categorical variables and t-test for continuous variables were used to identify variables associated with nutrition status. All p-values were two sided and statistical significance was considered at the level of 0.05. Analyses were conducted in R (R Core Team (2024)), version 4.4.1.

Results

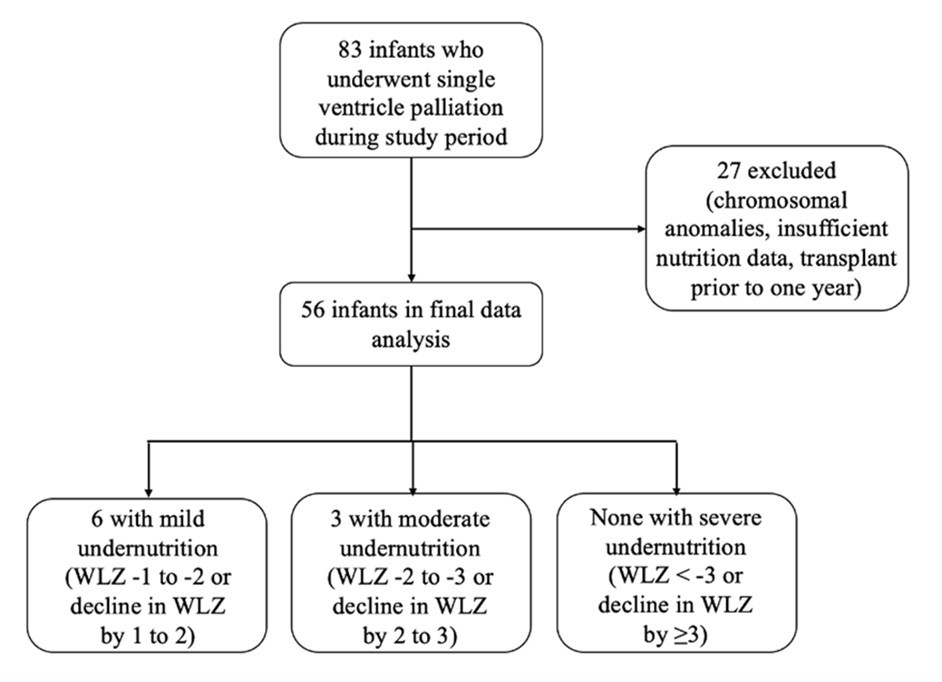

During the study period, 83 patients underwent single ventricle palliation. of these, 27 were excluded. Twenty-five patients were excluded based on the exclusion criteria described above and two patients underwent orthotopic heart transplant prior to one year and were also excluded from final data analysis. As a result, there were 56 total patients included in analysis (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.Study inclusion flowchart with undernutrition (specifically wasting) prevalence amongst our study population using World Health Organization (WHO) weight-for-length z-score (WLZ).

Anthropometric data

Nine patients (9/56, 16%) met WHO criteria for undernutrition. Six had mild undernutrition, three had moderate undernutrition, and none had severe undernutrition. Sex at birth and identified race were not associated with undernutrition. A greater proportion of patients identified as undernourished were born prior to 2013 (7/9, 78%), compared to those born after 2013 or in the second half of our study period (2/9, 22%, p=0.02). Further patient characteristics are demonstrated in Table 1.

Hospital courses and surgical management

Three infants (5%) were born preterm, and eight (15%) were born small for gestational age (SGA). Duration of initial hospitalization ranged from two days (in four patients without prenatal diagnosis) to 417 days. There was a median two-day duration of mechanical ventilation during initial hospitalization, with a range of 0 to 417 days. Median readmission rate within the first year was four. Neither duration of initial hospitalization nor hospital readmission rate was associated with nutrition status.

Initial surgical intervention varied widely (see Table 1), with twenty four patients (43%) undergoing Norwood procedure. Twelve patients had pulmonary artery (PA) banding, 33% of which were undernourished. This is compared to 11% of patients who did not have PA banding (p=0.09). Eight patients had a bidirectional Glenn (BDG) procedure as their first stage of palliation.

Table 1. Characteristics of study subjects. DORV = double outlet right ventricle, LV = left ventricle, AV = atrioventricular, TGA = transposition of the great arteries, BTT = Blalock-Taussig-Thomas, PDA = patent ductus arteriosus, PA = pulmonary artery, BDG = bidirectional Glenn.| Patient characteristics | |

|---|---|

| Sex | |

| Male | 36 (64%) |

| Female | 20 (36%) |

| Race | |

| White | 38 (68%) |

| Black/African American | 10 (18%) |

| Asian | 4 (7%) |

| American Indian | 2 (4%) |

| Hispanic/Latino | 1 (2%) |

| Mixed race | 1 (2%) |

| Cardiac diagnosis | |

| Hypoplastic left heart syndrome | 20 (36%) |

| Tricuspid atresia | 9 (16%) |

| Double inlet left ventricle | 9 (16%) |

| Hypoplastic right ventricle | 5 (9%) |

| DORV with LV hypoplasia | 5 (9%) |

| Unbalanced AV canal defect | 4 (7%) |

| L-TGA with pulmonary atresia | 2 (4%) |

| Ebstein anomaly | 1 (2%) |

| D-TGA with pulmonary atresia | 1 (2%) |

| Neonatal surgery | |

| Norwood procedure total | 24 (43%) |

| With BTT shunt | 5 (9%) |

| With Sano shunt | 14 (25%) |

| With PDA stent | 4 (7%) |

| With PA banding | 1 (2%) |

| Isolated pulmonary artery banding | 5 (9%) |

| Isolated BTT, Sano, or central shunt | 19 (34%) |

| No neonatal surgery | 8 (14%) |

| Surgical complications | |

| Diaphragmatic paralysis | 5 (9%) |

| Vocal cord paresis | 12 (21%) |

| Chylothorax | 7 (13%) |

| Primary nutrition source | |

| Breastmilk | 9 (16%) |

| Formula | 27 (48%) |

| Combination | 20 (36%) |

| Fortification | |

| ≥24 kcal/oz | 39 (71%) |

| <24 kcal/oz | 16 (29%) |

| Missing | 1 |

| Median age at initial discharge in days | 32.5 |

| Median hospitalizations by 12 months range | 4.0 1, 10 |

| Median age at BDG in months range | 7 3, 28 |

| BDG or Kawashima by one year | 46 (82%) |

| Pacemaker dependence | 2 (4%) |

| Tracheostomy dependence | 3 (5%) |

| At home oxygen use | 9 (16%) |

| G-tube placement | 28 (50%) |

BDG was completed at a median age of 7 months (range 3-28 months). Of those who underwent BDG after 6 months, 25% were undernourished at one year, versus 7.4% of those with BDG prior to 6 months (p=0.14). At one year of age, 45 patients (80%) had undergone BDG, with one patient status-post Kawashima procedure. Completion of BDG or Kawashima prior to one year was not associated with nutrition status.

Surgical complications in the first year included vocal cord paresis (n=12), diaphragmatic paralysis (n=5), and chylothorax (n=7). None of these variables were associated with undernutrition.

Nutritional support

Infants’ nutritional source included strictly formula (48%), strictly breast milk (16%), and combination breast milk and formula (36%). Source of nutrition was not related to nutrition status. Gastrostomy tube (G-tube) placement occurred prior to one year in 28 infants (50%). Neither fortification above 20 kcal/oz (p=0.71) nor G-tube placement (p=1.0) were associated with nutrition.

Cardiac variables

Twenty-nine patients (52%) had systemic right ventricular morphology and 27 patients (48%) had left ventricular morphology. A comprehensive list of cardiac diagnoses can be seen in Table 2, but included most commonly hypoplastic left heart syndrome (n=20, 36%), tricuspid atresia (n=9, 16%), and double inlet left ventricle (n=9, 16%). Neither ventricular morphology nor cardiac diagnosis was associated with nutrition status.

Table 2. Fisher’s exact analysis with undernourishment status as dependent variable. MAPCAs = major aortopulmonary collateral arteries, BDG = bidirectional Glenn, BTT = Blalock-Taussig-Thomas, PGE = prostaglandin E, AV = atrioventricular, Qp:Qs = ratio of pulmonary blood flow (Qp) to systemic blood flow (Qs), VEDP = ventricular end-diastolic pressure, VO2 = volume of oxygen (a marker of oxygen consumption), PVR = pulmonary vascular resistance.| Undernourished | Not undernourished | p-value | |

| Total study population | 9 (16%) | 47 (84%) | |

| Demographic variables | |||

| Born prior to 2013 | 7 (30%) | 16 (70%) | 0.02 |

| Male sex | 8 (22%) | 28 (78%) | 0.14 |

| White race | 5 (13%) | 33 (87%) | 0.45 |

| Cardiac variables | |||

| Right ventricular morphology | 5 (17%) | 24 (83%) | 1 |

| Heterotaxy | 0 (0%) | 7 (100%) | 0.58 |

| Hypoplastic left heart syndrome | 3 (15%) | 17 (85%) | 1 |

| MAPCAs | 3 (11%) | 25 (89%) | 0.47 |

| BDG after 6 months | 7 (25%) | 21 (75%) | 0.14 |

| BTT shunt (vs Sano shunt) | 2 (11%) | 17 (89%) | 0.7 |

| Pulmonary artery banding | 4 (33%) | 8 (67%) | 0.09 |

| Pulmonary hypertension | 0 (0%) | 10 (100%) | 0.19 |

| PGE-dependent | 5 (12%) | 36 (88%) | 0.23 |

| Systolic dysfunction at 6 months | 1 (33%) | 2 (67%) | 0.37 |

| Systolic dysfunction at 12 months | 2 (29%) | 5 (71%) | 0.25 |

| Aortic arch gradient >20 mmHg | 1 (11%) | 4 (80%) | 1 |

| Mild or greater AV regurgitation | 2 (14%) | 12 (86%) | 1 |

| Qp:Qs>1 | 1 (7%) | 14 (93%) | 1 |

| Mean right atrial pressure >10 mmHg | 0 (0%) | 10 (100%) | 1 |

| Systemic VEDP >10 mmHg | 0 (0%) | 10 (100%) | 1 |

| VO2 >160 mL/min/m2 | 1 (11%) | 8 (89%) | 0.48 |

| PVR >3 iWU | 0 (0%) | 2 (100%) | 1 |

| Cardiac index <3 L/min/m2 | 0 (0%) | 11 (100%) | 0.53 |

| Respiratory variables | |||

| Home supplemental oxygen | 0 (0%) | 9 (100%) | 0.33 |

| Tracheostomy | 0 (0%) | 3 (100%) | 1 |

| Pulmonology follow-up | 3 (19%) | 13 (81%) | 0.7 |

| Pulmonary medication use | 3 (9%) | 29 (91%) | 0.15 |

| Vocal cord paresis | 0 (0%) | 12 (100%) | 0.18 |

| Diaphragmatic paresis | 1 (20%) | 4 (80%) | 1 |

| Tracheobronchomalacia | 0 (0%) | 7 (100%) | 0.58 |

| Hypoxemia <70% | 1 (50%) | 1 (50%) | 0.12 |

| Neurologic variables | |||

| Hypoxic ischemic encephalopathy | 3 (21%) | 11 (78%) | 0.4 |

| Seizure disorder | 0 (0%) | 5 (100%) | 0.58 |

| Intraventricular hemorrhage | 1 (20%) | 4 (80%) | 1 |

| Gastrointestinal variables | |||

| Necrotizing enterocolitis | 0 (0%) | 4 (100%) | 1 |

| Gastroenterology follow-up | 2 (18%) | 9 (82%) | 1 |

| Feeding variables | |||

| Primarily breastfed | 1 (11%) | 8 (89%) | 1 |

| Fortification to 24 kcal/oz or more | 6 (15%) | 33 (85%) | 0.71 |

| G-tube placement | 4 (14%) | 24 (86%) | 1 |

| Other variables | |||

| Genetic syndrome | 3 (75%) | 1 (25%) | 0.01 |

| Speech therapy follow-up | 5 (14%) | 32 (86%) | 0.47 |

| Preterm birth | 0 (0%) | 3 (100%) | 1 |

| Small for gestational age | 0 (0%) | 8 (100%) | 0.58 |

| Hypothyroidism | 0 (0%) | 4 (100%) | 1 |

Echocardiographic variables included depressed systemic ventricular systolic function on echocardiogram closest to 6 months (n=3) and 12 months (n=6), aortic arch gradient >20 mmHg (n=5), and presence of atrioventricular valve regurgitation (n=14). There was no statistically significant association between these variables and nutrition status.

Hemodynamic variables were measured during cardiac catheterization. Thirty-two infants (57%) had cardiac catheterizations documented within the first year, the majority of which were pre-Glenn catheterizations. These hemodynamic variables can be visualized in Table 2. Pulmonary hypertension, defined by transpulmonary gradient ≥6 mmHg during cardiac catheterization20, was identified in 10 infants (18%) prior to one year.

Respiratory variables

Nine infants (16%) required home supplemental oxygen: five via low-flow nasal cannula, three via tracheostomy, and one via continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP). None of these infants were undernourished at one year (p=0.33). There was no association between nutrition status and systemic hypoxemia (oxygen saturation <70%) during cardiac catheterization (n=2, p=0.12). Sixteen infants had regular pulmonology follow-up, and 32 received pulmonary medication during the first year of life. The most commonly used medications were short-acting beta-2 agonists, followed by inhaled corticosteroids and pulmonary vasodilators.

Pulmonology follow-up slightly declined over time: 35% of infants born prior to 2013 had outpatient visits, compared to 24% of those born in 2013 or later (p=0.39). Nutritional status was not significantly associated with pulmonology follow-up (p = 0.71).

Among those who used pulmonary medications, 9.4% were undernourished, versus 25% among those that did not (p = 0.15). There were no significant associations between undernutrition and use of bronchodilators (p = 0.41) or pulmonary vasodilators alone (p = 0.37).

Discussion

The rate of mild undernutrition in our study population was 16% (WLZ ≤ -1), while the rate of moderate to severe undernutrition was 5% (WLZ ≤ -2). These rates are substantially lower than previously reported figures (18-24%) for moderate to severe undernutrition amongst this patient population5, 14. Below average WLZ (defined as a negative z-score) was present in 50% of patients, which is by definition consistent with the average global rates based on WHO data. Our study also demonstrated that there has been improvement in nutrition status for infants with SV over the past 10 years at our institution (p=0.02). This progress may be attributed to various factors, such as global improvements in SV patient care, advances in surgical techniques, enhanced nutritional monitoring, and refinements in multisystemic support strategies.

Demographic factors were not associated with nutrition among our sample population. Prior studies have demonstrated impaired growth for “non-Caucasian” patients at time of BDG4. While our study did not demonstrate similar associations, race as a social construct can have profound impacts on morbidity and mortality in CHD21. The impact of race and socioeconomic status requires ongoing investigation to address persistent disparities, particularly as methods for collecting race data evolve.

Nutritional interventions

The benefits of nutritional interventions for patients with congenital heart disease have long been recognized. Previous studies on patients with SV physiology have shown that fortification5, 7, 23 and enteric tube use4 are associated with better nutritional outcomes. Other studies12, 19 align more closely with our findings, which did not reveal similar associations. This discrepancy may reflect early and appropriate nutritional interventions such as fortification for infants during our study period. Breastfeeding is thought to protect against malnutrition4, partly because the composition of breast milk aligns with the caloric needs of infants according to their gestational age. About 52% of the cohort received regular breast milk, and no such association was demonstrated.

Cardiac variables

Although the cardiac variables examined did not significantly impact nutritional status, several noteworthy associations were observed. It is widely recognized that catch-up weight gain occurs most notably after BDG7, 14, 22. Early surgical intervention is thought to provide benefits through early elimination of volume overload and cyanosis5. Although not statistically significant, a higher percentage of infants who underwent BDG after 6 months were undernourished compared to those who underwent the procedure earlier. This likely reflects improved catch-up growth following BDG, potentially due to a decreased metabolic rate resulting from the ventricular offloading that BDG provides. Improved oxygenation may also play a role.

Although right ventricular morphology was not significantly associated with nutritional status, a greater proportion of these patients had negative WLZ scores compared to those with left ventricular morphology (62% vs. 37%). Prior studies have demonstrated that those with morphologic right ventricles are more prone to ventricular dysfunction24, 25, which may have long-term impacts on systemic perfusion and, consequently, growth. In our cohort, right ventricular morphology was significantly associated with depressed systolic function; all six infants with depressed function had a primary right ventricle (p=0.02), suggesting this may be a contributing mechanism.

Respiratory variables

Arguably the most notable findings of this study involved respiratory variables. Infants who regularly received pulmonary medications in the first year had lower rates of undernutrition (9.4% vs. 25%). This may reflect benefits from improved ventilation, pulmonary clearance, and regular pulmonary surveillance. Prior studies have documented detrimental effects of elevated mean pulmonary arterial pressures on nutrition4, suggesting pulmonary vasodilator use may be nutritionally beneficial, though no significant association was observed in our cohort.

While outpatient pulmonology follow-up was not associated with nutritional outcomes, it is difficult to interpret the true impact of pulmonology involvement due to limited availability of these services at our institution during parts of the study period.

Supplemental oxygen use also appeared related to nutritional outcomes. Of the nine patients that used at home supplemental oxygen, none were undernourished and only one patient had negative WLZ. We defined supplemental oxygen as the use of an interface that provides oxygen at a fraction of inspired oxygen (FiO2) greater than 21%. While the modalities of respiratory support offer multiple potential physiology benefits, there is conflicting evidence regarding the nutritional impacts of increased systemic oxygenation.

Some studies3, 4, 19 have demonstrated worsened nutritional outcomes with higher systemic oxygenation, thought to be related to detrimental impacts of pulmonary over circulation, increased ventricular volume load, and decreased splanchnic perfusion26. Contrasting studies5, 6, 7, 22, 27 have suggested that chronic hypoxemia, typically below an oxygen saturation of 75%, is associated with poorer nutritional outcomes.

These conflicting findings highlight the complex physiological adaptations in patients with SV living with chronic hypoxemia. While these patients’ hypoxemic respiratory drive is typically depressed28, 29, chronic hypoxemia also increases peripheral chemoreceptor sensitivity to hypercapnia, which can increase ventilatory drive and metabolic demand30. Molecular adaptations, including alteration in ATP utilization and hypoxia-inducible factor (HIF-1) activation, lead to a relative catabolic state with decreased lipid storage and protein synthesis31-32. Additionally, chronic hypoxemia can delay bone age33, 34 and have disproportionate effects on linear growth3. This increases the risk of stunting but may actually increase WLZ.

While physiologic patterns have been broadly identified, the long-term nutritional effects of chronic hypoxemia remain poorly understood in pediatric populations. Studies involving cohorts of adults with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) have shown that chronic hypoxemia negatively affects nutrition32, 35, with evidence also supporting the nutritional benefits of non-invasive positive pressure ventilation (NIPPV) in this group36. In children with cerebral palsy, tracheostomy use has been associated with mixed nutritional outcomes37, 38. However, to our knowledge, no studies have specifically examined the impact of hypoxemia or respiratory support on nutrition in patients with SV physiology.

Outside of oxygenation, potential benefits of respiratory support also include improved ventilation, leading to decreased energy expenditure from work of breathing39. This could explain some of the nutritional benefits demonstrated in this study. We did not, however, find a relation between oxygen consumption (VO2), a metric for energy expenditure, and nutrition status in our study.

While our study did not find a significant association between hypoxemia and nutritional status, this may be attributable to limited statistical power due to sparse hemodynamic data among undernourished patients. This limits conclusions that can be made regarding the effects of supplemental oxygen amongst our cohort. Nonetheless, the observed trends, particularly the potential nutritional benefit of supplemental oxygen, underscore the need for larger, prospective studies to better characterize the complex interplay between respiratory support, systemic oxygenation, and growth in patients with single ventricle physiology.

Study Limitations

The retrospective design of the study limits conclusions about causation between identified variables and undernutrition. As this was a single-center study, the findings may not be generalizable to other institutions due to variations in patient cohorts and management strategies. While there were clinically significant associations observed in this study, the relatively small cohort, particularly within the subgroups of moderate and severe undernutrition, could have limited statistical power.

Excluding patients with unavailable nutritional data or those deceased before one year of age, which accounted for 33% of the target population, may have introduced selection bias, potentially underrepresenting the most vulnerable patients in this cohort. Anthropometric measurements were restricted to a single time point around one year of age, limiting the ability to assess longitudinal growth patterns and the impact of interventions over time. The collection of race and gender data does not account for other social determinants of health, such as socioeconomic status, parental education, or access to healthcare, which may significantly influence nutritional outcomes.

Finally, the study spanned two decades (2003–2023), during which advancements in surgical techniques, nutritional practices, and postoperative care may have influenced outcomes, introducing temporal variability into the results. These limitations should be considered when interpreting the findings, as they may affect the study's applicability to broader populations and its ability to inform clinical practice.

Conclusion

This study investigated associations and potential protective factors against undernutrition in infants with single ventricles. Undernutrition rates significantly declined during the study period. Although no statistically significant associations were found, respiratory support, especially the use of supplemental oxygen, was associated with adequate nutrition status. This highlights the complex interplay between cardiorespiratory function and growth. Our conclusions are limited by small sample sizes, reinforcing the need for larger studies to further explore how respiratory interventions might impact nutrition in this population.

Acknowledgements

First, the authors acknowledge the many patients who generously allowed their health information to be used in this research study. The authors would also like to thank the University of Minnesota and Eastern Virginia Medical School for their support of this research.

References

- 1.Khairy P, Poirier N, Mercier L A. (2007) . Univentricular heart.DOI: 10.1161 CIRCULATIONAHA.105.592378. Circulation 115(6), 800-812.

- 2.Kaulitz R, Hofbeck M. (2005) Current treatment and prognosis in children with functionally univentricular hearts. DOI: 10.1136/adc.2003.034090. Archives of Disease in Childhood 90(7), 757-762.

- 3.Eynde J Van den, Bartelse S, Rijnberg F M, Kutty S, Jongbloed MRM. (2023) Somatic growth in single ventricle patients: A systematic review and meta-analysis. DOI: 10.1111/apa.16562. Acta Paediatrica , Oslo, Norway: 112(2), 186-199.

- 4.Anderson J B, Beekman R H, Eghtesady P, Kalkwarf H J, Uzark K et al. (2010) Predictors of poor weight gain in infants with a single ventricle. DOI: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2010.04.012. , The Journal of Pediatrics 157(3), 407-413.

- 5.Luo W Y, Xu Z M, Zhang Y Y, Hong L, Zhang M J. (2020) . The Nutritional Status of Pediatric Patients with Single Ventricle Undergoing a Bidirectional Glenn Procedure. DOI: , Pediatric Cardiology 41(8), 10-1007.

- 6.A M Shine, Foyle L, Gentles E, Ward F, C J McMahon. (2021) . Growth and Nutritional Intake of Infants with Univentricular Circulation. DOI: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2021.06.037. The Journal of Pediatrics 237, 79-86.

- 7.Vogt K N, Manlhiot C, G Van Arsdell, Russell J L, Mital S. (2007) Somatic growth in children with single ventricle physiology impact of physiologic state. DOI: 10.1016/j.jacc.2007.07.050. , Journal of the American College of Cardiology 50(19), 1876-1883.

- 8.Ezzat M A, Albassam E M, Aldajani E A, Alaskar R A, E B Devol. (2022) Implementation of new indicators of pediatric malnutrition and comparison to previous indicators. DOI: 10.1016/j.ijpam.2022.12.003. , International Journal of Pediatrics & Adolescent Medicine 9(4), 216-224.

- 9.Becker P, Carney L N, Corkins M R, Monczka J, Smith E. (2015) Consensus statement of the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics/American Society for Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition: Indicators recommended for the identification and documentation of pediatric malnutrition (undernutrition). DOI: 10.1177/0884533614557642 . Nutrition in Clinical Practice: Official Publication of the American Society for Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition 30(1), 147-161.

- 10. (2025) . from https://data.unicef.org/topic/nutrition/malnutrition/ , Unicef Data. Retrieved February 6.

- 11.Davis D, Davis S, Cotman K, Worley S, Londrico D. (2008) Feeding difficulties and growth delay in children with hypoplastic left heart syndrome versus d-transposition of the great arteries. DOI: 10.1007/s00246-007-9027-9. Pediatric Cardiology. 29(2), 328-333.

- 12.Medoff-Cooper B, Ravishankar C. (2013) Nutrition and growth in congenital heart disease: A challenge. in children. DOI: 10.1097/HCO.0b013e32835dd005. Current Opinion in Cardiology 28(2), 122-129.

- 13.Ravishankar C, Zak V, Williams I A, Bellinger D C, Gaynor J W. (2013) Association of Impaired Linear Growth and Worse Neurodevelopmental Outcome in Infants with Single Ventricle Physiology: A Report from the Pediatric Heart Network Infant Single Ventricle Trial. DOI: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2012.07.048. , The Journal of Pediatrics 162(2), 250-256.

- 14.Costello C L, Gellatly M, Daniel J, Justo R N, Weir K. (2015) . Growth Restriction in Infants and Young Children with Congenital Heart Disease. DOI: 10.1111/chd.12231. Congenital Heart Disease 10(5), 447-456.

- 15.Laraja K, Sadhwani A, Tworetzky W, Marshall A C, Gauvreau K. (2017) Neurodevelopmental Outcome in Children after Fetal Cardiac Intervention for Aortic Stenosis with Evolving Hypoplastic Left Heart Syndrome. DOI: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2017.01.034. , The Journal of Pediatrics 184, 130-136.

- 16.Dykman R A, Casey P H, Ackerman P T, McPherson W B. (2001) Behavioral and cognitive status in school-aged children with a history of failure to thrive during early childhood. DOI: 10.1177/000992280104000201. Clinical Pediatrics. 40(2), 63-70.

- 17.Corman L C. (1985) Effects of Specific Nutrients on the Immune Response: Selected Clinical Applications. , DOI:, Medical Clinics of North America 69(4), 10-1016.

- 18.Anderson J B, Beekman R H, Border W L, Kalkwarf H J, Khoury P R. (2009) Lower weight-for-age z score adversely affects hospital length of stay after the bidirectional Glenn procedure in 100 infants with a single ventricle. DOI: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2009.02.033. , The Journal of Thoracic and Cardiovascular Surgery 138(2), 397-404.

- 19.Kelleher D K, Laussen P, Teixeira-Pinto A, Duggan C. (2006) Growth and correlates of nutritional status among infants with hypoplastic left heart syndrome (HLHS) after stage 1 Norwood procedure. , DOI: 10.1016/j.nut.2005.06.008. Nutrition 22(3), 237-244.

- 20.Jone P-N, Ivy D D, Hauck A, Karamlou T, Truong U. (2023) . Pulmonary Hypertension in Congenital Heart Disease: A Scientific Statement From the American Heart Association. DOI: 10.1161/HHF.0000000000000080. Circulation: Heart Failure 16(7), 00080.

- 21.Duong S Q, Elfituri M O, Zaniletti I, Ressler R W, Noelke C. (2023) . Neighborhood Childhood Opportunity, Race/Ethnicity, and Surgical Outcomes in Children With Congenital Heart Disease. DOI: 10.1016/j.jacc.2023.05.069 , Journal of the American College of Cardiology 82(9), 801-813.

- 22.Hehir D A, Cooper D S, Walters E M, Ghanayem N S. (2011) Feeding, growth, nutrition, and optimal interstage surveillance for infants with hypoplastic left heart syndrome. DOI: 10.1017/S1047951111001600. Cardiology in the Young 21, 59-64.

- 23.Pillo-Blocka F, Adatia I, Sharieff W, McCrindle B W, Zlotkin S. (2004) Rapid advancement to more concentrated formula in infants after surgery for congenital heart disease reduces duration of hospital stay: A randomized clinical trial. DOI: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2004.07.043. , The Journal of Pediatrics 145(6), 761-766.

- 24.Graham T P. (1991) Ventricular performance in congenital heart disease. DOI: 10.1161/01.cir.84.6.2259. Circulation 84(6), 2259-2274.

- 25.Sano T, Ogawa M, Taniguchi K, Matsuda H, Nakajima T. (1989) Assessment of ventricular contractile state and function in patients with univentricular heart. DOI: 10.1161/01.cir.79.6.1247. Circulation 79(6), 1247-1256.

- 26.P S Rao. (2021) . Single Ventricle-A Comprehensive Review. DOI: 10.3390/children8060441. Children , (Basel, Switzerland) 8(6), 441.

- 27.Leitch C A, Karn C A, Peppard R J, Granger D, Liechty E A. (1998) Increased energy expenditure in infants with cyanotic congenital heart disease. , DOI: 133(6), 10-1016.

- 28.Liang P J, Bascom D A, Robbins P A. (1997) Extended models of the ventilatory response to sustained isocapnic hypoxia in humans. DOI: 10.1152/jappl.1997.82.2.667. Journal of Applied Physiology , Bethesda, Md: 82(2), 667-677.

- 29.Mouradian G C, Lakshminrusimha S, Konduri G G. (2021) . Perinatal Hypoxemia and Oxygen Sensing. DOI: 10.1002/cphy.c190046. Comprehensive Physiology 11(2), 1653-1677.

- 30.Cherniack N S, Edelman N H, Lahiri S. (1970) Hypoxia and hypercapnia as respiratory stimulants and depressants. , Respiration Physiology 11(1), 10-1016.

- 31.Fontaine E, Leverve X. (2008) Basics in clinical nutrition: Metabolic response to hypoxia. DOI:. 10.1016/j.eclnm.2008.07.001. European E-Journal of Clinical Nutrition and Metabolism 3(6), 285-288.

- 32.Raguso C A, Luthy C. (2011) Nutritional status in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease:. Role of hypoxia. DOI: 10.1016/j.nut.2010.07.009. Nutrition , Burbank, Los Angeles, County, Calif.) 27(2), 138-143.

- 33.Witzel C, Sreeram N, Coburger S, Schickendantz S, Brockmeier K et al. (2006) Outcome of muscle and bone development in congenital heart disease. DOI: 10.1007/s00431-005-0030-y. , European Journal of Pediatrics 165(3), 168-174.

- 34.Danilowicz D A. (1973) Delay in bone age in children with cyanotic congenital heart disease. DOI: 10.1148/108.3.655. Radiology 108(3), 655-658.

- 35.Westerterp K R. (2001) Energy and Water Balance at High Altitude. DOI: 10.1152/physiologyonline.2001.16.3.134. Physiology 16(3), 134-137.

- 36.Budweiser S, Heinemann F, Meyer K, Wild P J, Pfeifer M. (2006) Weight gain in cachectic COPD patients receiving noninvasive positive-pressure ventilation. Respiratory Care. 51(2), 126-132.

- 37.Henningfeld J, Lang C, Erato G, Silverman A H, Goday P S. (2021) Feeding Disorders in Children With Tracheostomy Tubes. DOI: 10.1002/ncp.10551. Nutrition in Clinical Practice: Official Publication of the American Society for Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition 36(3), 689-695.